In my previous posts, I outlined how hot and humid climates increase the rate of dehydration during exercise. I also provided strategies to maintain proper fluid balance in these conditions. I would now like to explore the concept of heat acclimation and methods to overcome and adapt to hot environments.

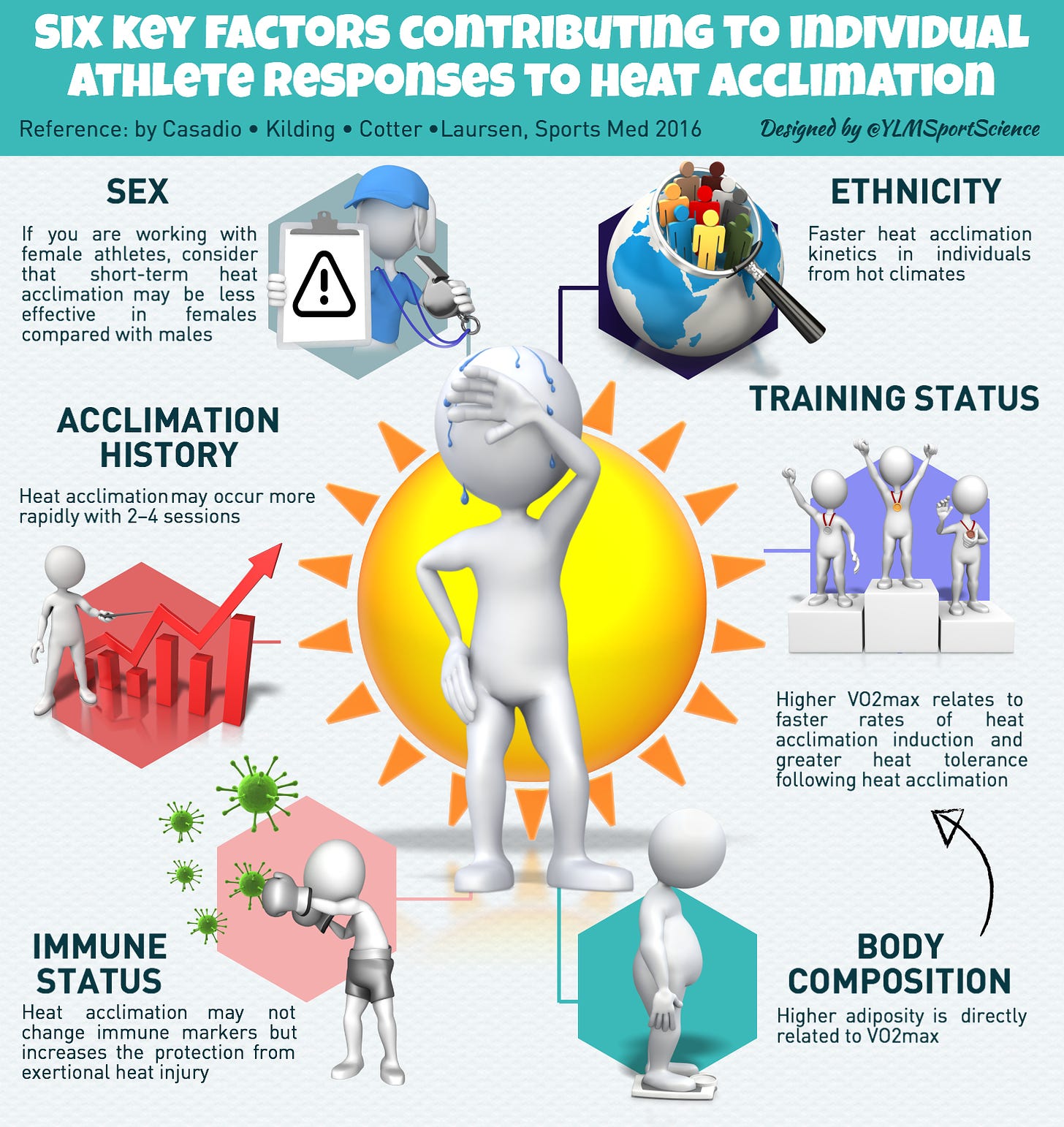

Heat acclimation can be defined as repeated bouts of prolonged low intensity exercise in the heat causing positive physiological adaptations (Kenney, Wilmore, & Costill, 2012). When performed correctly, there can be adaptive responses in plasma volume, cardiovascular function, sweating and skin blood flow (Kenney et al., 2012).

Adaptation to heat takes time. Kenney et al. (2012) suggests that it may take anywhere from 9-14 days to adjust to hotter climates. Moreover, time spent in hot climates need not be long. Kenney et al. (2012) suggested one hour per day while exercising as a recommended guideline to allow for adaptive responses.

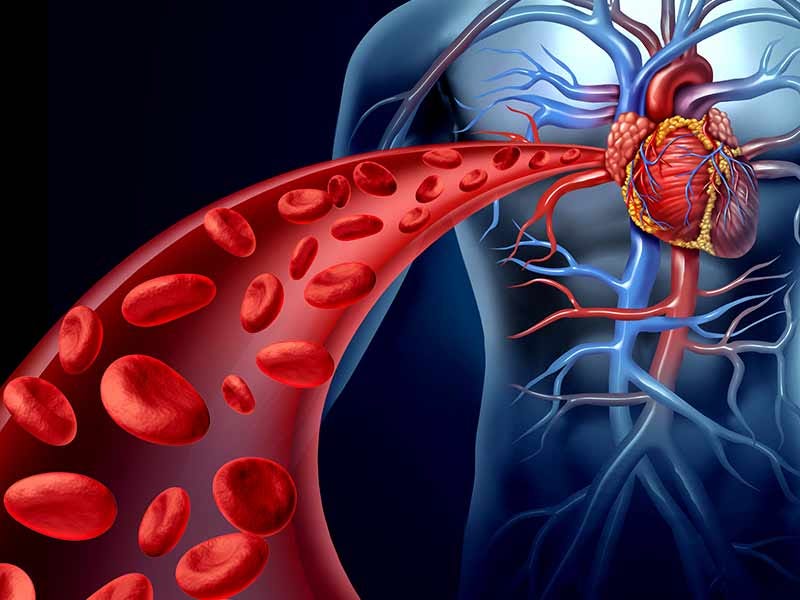

One adaptation during heat acclimation is an increase in blood volume that occurs the first 1-3 days of heat exposure and exercise. This is important because it allows blood to flow to muscles and to the skin to maintain core temperature. It also places less strain on the heart. When blood volume is low at a given intensity, the heart compensates by increasing its rate to maintain cardiac output. When blood volume is higher, the heart does not need to beat as fast, saving energy and extending the onset of fatigue (Kenney et al., 2012).

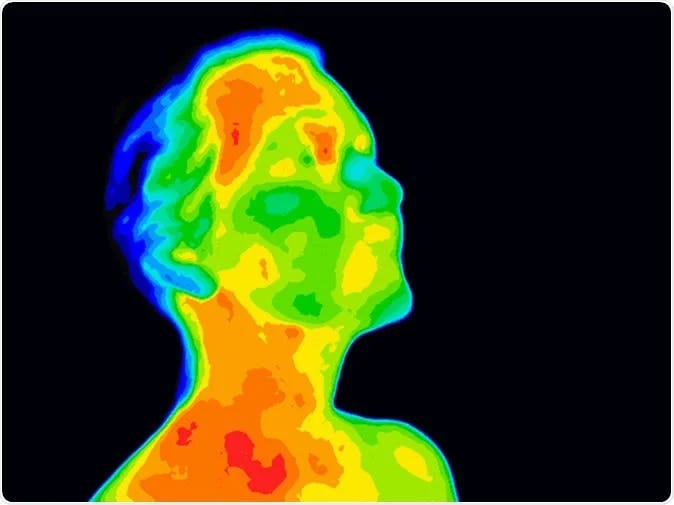

Another adaptive response to heat acclimation is a reduction of core temperature. One reason that an acclimated person will experience longer bouts of exercise at a lower core temperature than an unacclimated person might be due to onset of sweating (Kenney et al., 2012). That is, an acclimated person will begin sweating earlier. This allows the body to maintain its core temperature, and better attenuate increases in body temperature from exercise metabolism. In turn, an acclimated person will be able to continue exercise at a given intensity for a longer period of time.

Finally, a third adaptive response to exercise in hot environments would be the distribution of sweat. In acclimated people, sweat is more evenly distributed to areas of the body that will dissipate heat the quickest, namely the arms and legs (Kenney et al., 2012). Another advantage of an acclimated person would be the reduction of sodium in the sweat compared to an unacclimated person (Kenney et al., 2012). This would be beneficial, as reducing electrolyte losses will enable muscle contraction to occur longer and more forcefully before the initiation of fatigue.

In conclusion, understanding the deleterious effects of exercising in hot environments enables me to strategize solutions for my clients. In my profession as a Kinesiologist, I have individuals who routinely exercise while on vacation. Often, they are in climates that are hot. Having this knowledge empowers my clients to plan their excursions with more structure, wisdom, and safety at hand.

References

Kenney, W. L., Wilmore, J. H., & Costill, D. L. (2012). Physiology of sport and exercise (5th ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

-Michael McIsaac