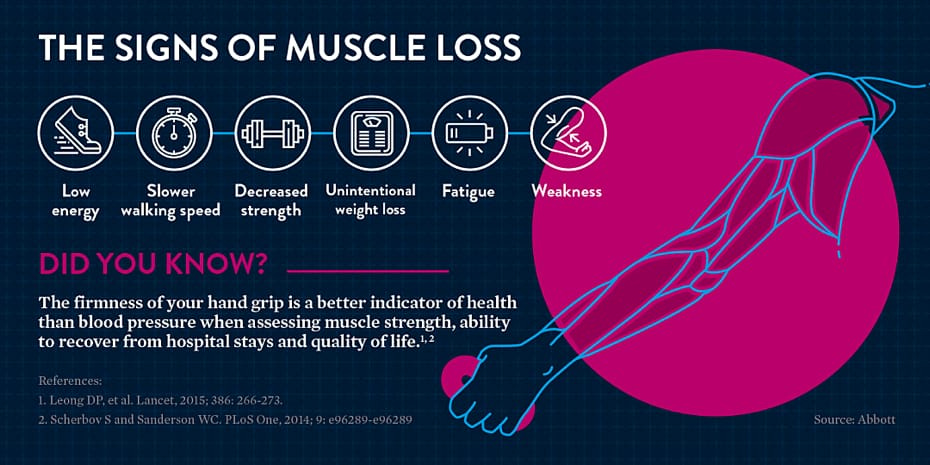

Aging brings with it, steady decrements in strength. Its etiology is connected to multiple sources such as inactivity, down-regulated hormonal levels, poor nutritional habits and sarcopenia (Kenney, Wilmore, & Costill, 2012). Two of the most debilitating consequences associated with aging are losses of hand dexterity and grip strength. In the following paragraphs I would like to cover a brief overview of the muscles involved in gripping, common forms of gripping, and solutions to mitigate strength losses in the elderly.

The hand has unusual abilities, ranges of motion, and fine motor control when compared to other limbs and muscles of the body. It is also the primary way in which we interact with our environment (i.e., driving, cooking, lifting, brushing teeth etc…). When considering a strong grip such as the cylindrical grip or hook grip, what muscles are involved?

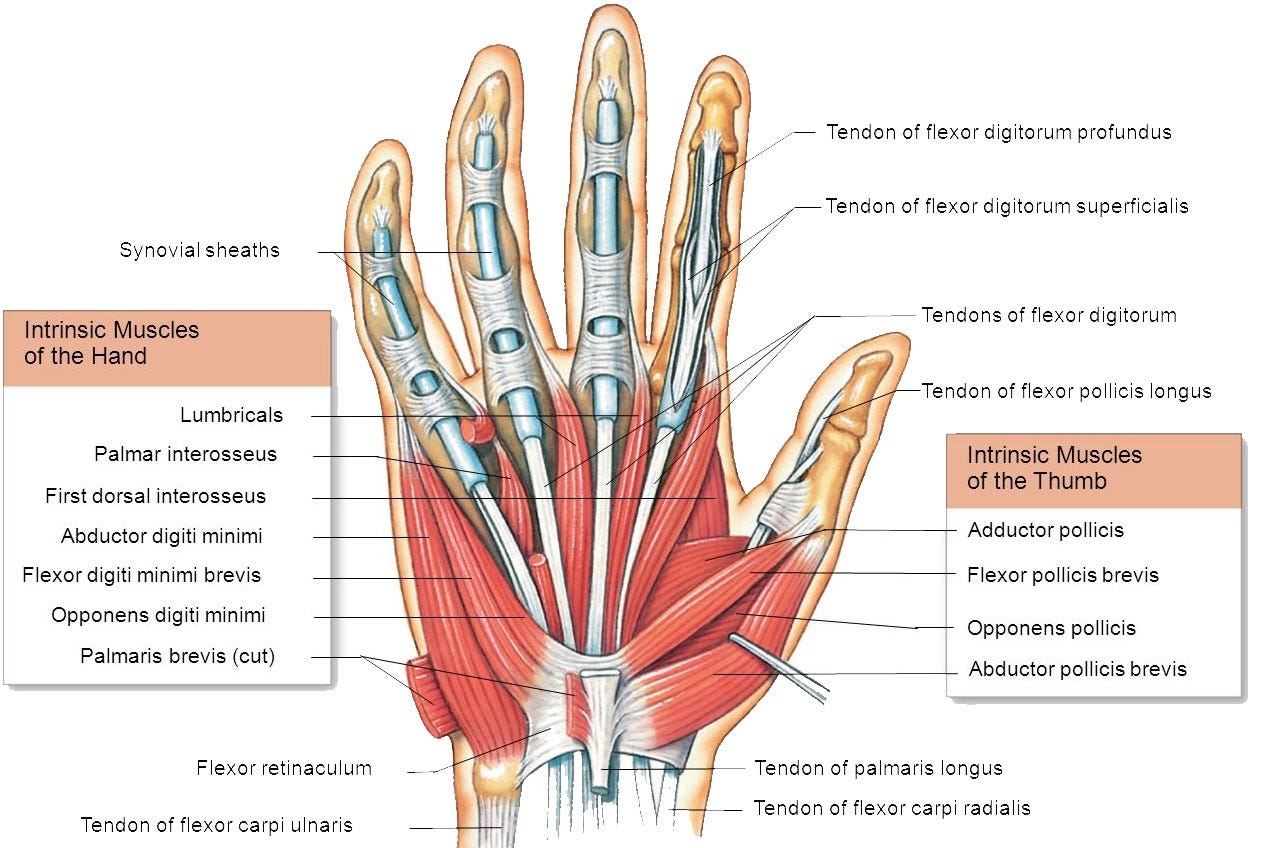

Having a stable and neutral wrist during gripping motion is important; it also allows the gripping muscles within the forearm and hand to have optimal actin and myosin crossbridging for maximal force production (Baechle & Earle, 2000). The flexor carpi ulnaris is a muscle that plays a larger role in stabilization of the wrist. If it is weak, a person may lack the ability to stabilize the wrist and thusly produce a forceful grip (Bliven, 2014). Having considered a strong wrist to allow grip to occur, what are the muscles involved in gripping motions?

Flexion of all phalangeal joints is of utmost importance in closing a grip around objects (i.e., carrying a suitcase or groceries). Muscles involved in this would be: flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, abductor pollicis longus, flexor digitorum superficialis, and flexor digitorum profundus (Bliven, 2014). It is also important for the thumb to adduct and flex around the object as well (Bliven, 2014). In this case, muscles involved are the adductor pollicis brevis and opponens pollicis. This outline is by no means a complete explanation of the complexities of gripping motions, but rather a brief overview to appreciate the intricate nature of the hand. However, considering the functional anatomy, how might we target most or all of these muscles if they are weak?

In my practice, I prefer exercises that are simple to remember, accessible and easy to implement. If I have a client with a compromised grip, I like to use a method that captures most of the flexion motions in the aforementioned paragraph. I use a tool known as captains of crush (Ironmind, 2014). I like these because they can progressively increase loads imposed upon the hand in approximately 20-pound increments, they are relatively cheap (i.e., 20 dollars), and very durable. Generally, grip strength is trained at the end of the workout. This is done because I do not want the gripping muscles to become prematurely fatigued when training other muscles and movements patterns in the body that require adequate grip strength. Repetitions are generally low (i.e., 3-5 repetitions) to target type 2 muscle fibers involved in higher force productions (Kenney et al., 2012).

Strength losses amongst the elderly is a condition that many are afflicted with. If we can intervene with methods that are simple, efficacious and easy to implement, we stand a greater chance in assisting and improving activities associated with daily living.

References

Baechle, T. R., & Earle, R. W. (2000). Essentials of strength training and conditioning (2nd ed). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Bliven, K. (2014). Functional anatomy of the forearm, wrist, and hand. Part 1: Anatomy, and. Part 2: Muscle mechanics [Slideshow Presentation].

Ironmind (2014). Retrieved January 25, 2014, from http://www.ironmind.com/ironmind/opencms/Main/captainsofcrush.html

Kenney, W. L., Wilmore, J. H., & Costill, D. L. (2012). Physiology of sport and exercise (5th ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

-Michael McIsaac