In my last post, I noted that modern Western diets, including macronutrient ratios and macronutrient quality, were substantially different than the hominin diets 10,000 years ago (Ilich, Kelly, Kim, & Spicer, 2014). Of particular interest is the stratification of then and now between daily carbohydrate consumption and carbohydrate quality. In the following sections, I would like to explore the physiological utility of carbohydrates, carbohydrate types, and mismanagement of this macronutrient in the modern diet.

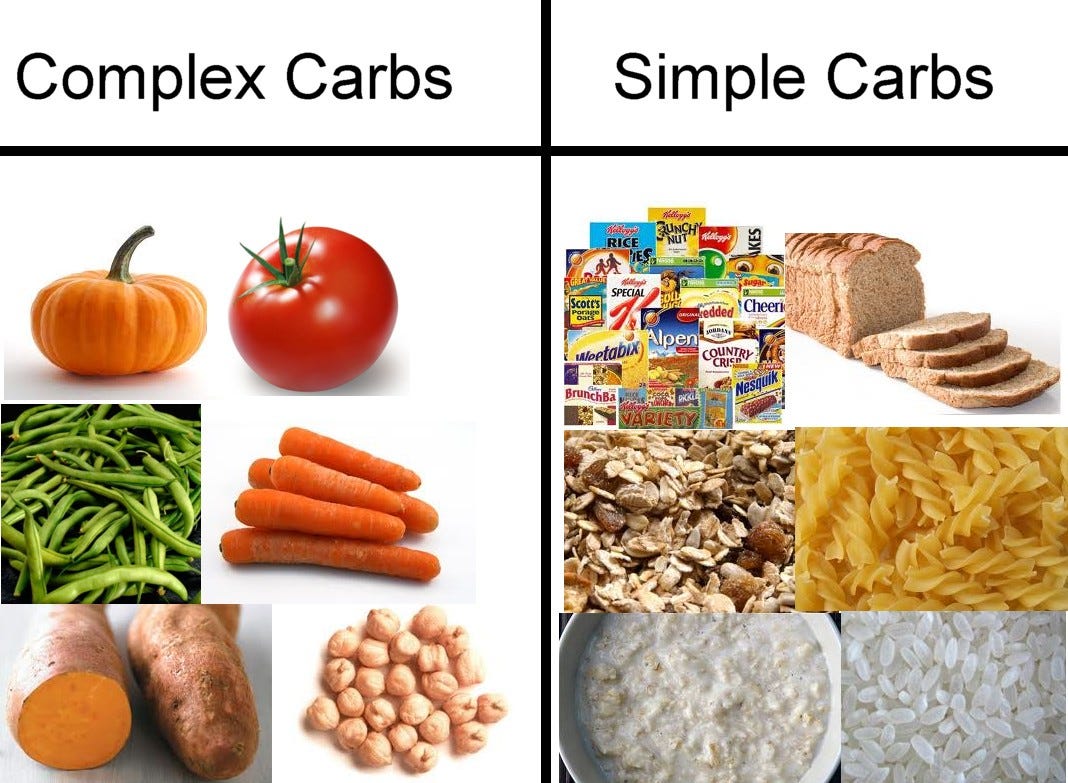

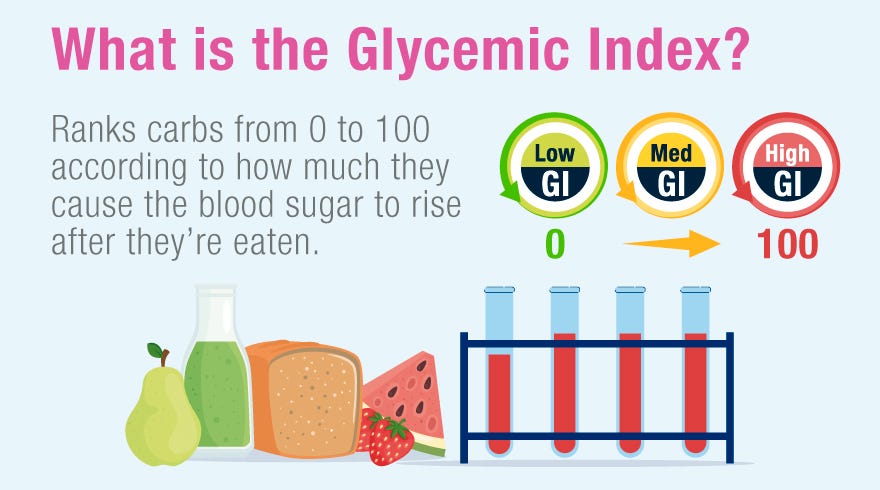

Carbohydrates were, and continue to be, a component in human nutrition. “Good” or “bad” carbohydrates may be an oversimplified and anthropomorphized way of viewing this macronutrient. Instead, we might view them first as a source of energy that can come in differing levels of quality (i.e., complex carbohydrates versus refined sugars). We may also view their quality by their glycemic index (GI). Insulin is a hormone involved in energy metabolism playing a chief role in enhancing the utilization of glucose in the muscle and liver (Pereira, Almeida, Alfenas, & Cassia, 2014). What then, are the physiological challenges associated with low and high GI foods?

Lower GI carbohydrates places less demand on the pancreas to produce insulin and create a longer lasting sensation of satiety. Conversely, refined carbohydrates (i.e., high GI) undergo accelerated digestion and absorption, leading to hunger and increased food consumption.

This chronic process has been associated with obesity, insulin resistance, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes (Pereira et al., 2014). Carbohydrate type is one factor that must be considered when analyzing its effects on the human body. In the following sections, I would to consider the total daily consumption of carbohydrates, and their relationships to other macronutrients.

Three macronutrients exist in the human diet: protein, fats, and carbohydrates. If we use the paleolithic template as a foundation to compare modern human diets against each other, it allows us appreciate the differences and possible causes of modern day chronic diseases. It also allows us to contextualize carbohydrates in our modern diets. During the paleolithic period, most people with few exceptions, consumed all three macronutrients.

It has been suggested that during the paleolithic period, people consumed approximately 35% of their calories from fats, 30% from proteins, and 35% from carbohydrates (Eaton, 2006). Thus, there exists support for consumption of carbohydrates in our distant past. There are at least two characteristics, however, that are different in the paleolithic diet; ancestral humans consumed less carbohydrates than the modern world, and they consumed more complex/nutrient dense carbohydrates (Bastos, Villalba, O’Keefe, Lindeberg, & Cordain, 2011).

Modern diets tend to include over 70% of total energy from refined sugars, refined vegetable oils, processed foods, and alcohol (Ilich et al., 2014). As high as 50% of total daily calories come from refined carbohydrates in the standard American diet, with cereal grains (85% refined) being the dominant carbohydrate source (Konner & Eaton, 2010). Thus, modern diets have approximately 15% more daily calories coming from carbohydrates compared to the paleolithic period, and most of the carbohydrate sources are refined, contributing to and exacerbating pro-inflammatory markers in the body (Pereira et al., 2014).

In conclusion, although the paleolithic period and modern day both share carbohydrates in the human diet, western civilizations tend to chronically over consume carbohydrates beyond ancestral macronutrient levels, as well as overindulgence in refined sources. When combined, these traits drastically separate themselves from the ways in which our paleolithic ancestors implemented and consumed carbohydrates. Thus, it becomes apparent, and imperative, to strongly reconsider our proclivities towards chronic over consumption of this aforementioned macronutrient, and rethink its place, quality and portion, in the modern diet.

References

Carrera-Bastos, P., Fontes-Villalba, M., O’Keefe, J.H., Lindeberg, S., & Cordain, L. (2011). The western diet and lifestyle and diseases of civilization. Research Reports in Clinical Cardiology, 2, 15-35.

Eaton, S.B. (2006). The ancestral human diet: What was it and should it be a paradigm for contemporary nutrition? Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 65, 1-6.

Ilich, J.Z., Kelly, O.J., Kim, Y., & Spicer, M.T. (2014). Low-grade chronic inflammation perpetuated by modern diet as a promoter of obesity and osteoporosis. Archives of Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology, 65(2), 139-148.

Konner, M., & Eaton, S.B. (2010). Paleolithic nutrition. Twenty-five years later. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 25(6), 594-602.

Pereira, F., Almeida, P.G., Alfenas, C.G., & Cassia, R. (2014). Glycemic index role on visceral obesity, subclinical inflammation and associated chronic diseases. Nutricon Hospitalaria, 30(2), 237-243.

-Michael McIsaac