Roberg and Landwehr (2002) indicated the ambiguous history, poor predictability, and misuse of the maximum heart rate prediction equation (HRmax=220-age) commonly taught and used in academic institutions. Unveiling the aforementioned truths is a reminder that dogmatic practices can insidiously permeate throughout a field in an unknown, and undetected fashion. Considering the lack of scientific merit in the HRmax=220-age equation questions how to best condition the cardiovascular system in a way that is effective and safe. The following sections will explore how this author helps clientele condition their cardiovascular systems through implementation of rate of perceived exertion (RPE), as well as why clients prefer the aforementioned approach

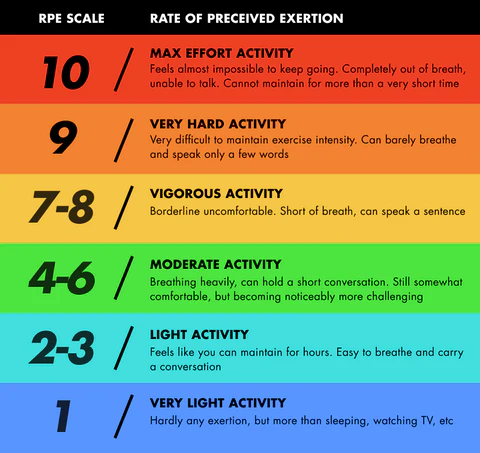

The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) defines RPE as measuring feelings of effort, strain, discomfort, and/or fatigue experienced during both aerobic and resistance training (ACSM, 2015). The scale was developed by a Swedish psychologist, Gunner Borg, and begins at level 6 (L6) continuing to L20 in one-unit increments (ACSM, 2015). RPE is broken down as follows: L6-no exertion, L7-extremely light, L8, L9-very light, L10, L11-light, L12, L13-somewhat hard, L14, L15-hard (heavy), L16, L19-extremely hard, L20-maximal exertion (ACSM, 2015). ACSM (2015) stated that there is a reasonable linear relationship with oxygen uptake and heart rate. Thus, RPE can be used to guide the progression of cardiovascular exercises. The following will consider the research of Aamot, Forbord, Karlsen, and Støylen (2014), and relationships between RPE and direct heart rate measurements.

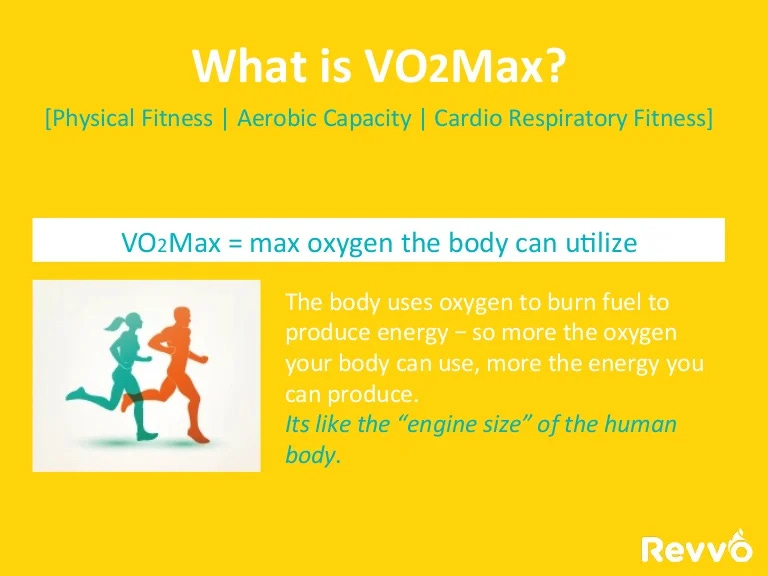

Cardiovascular exercise has been shown to help improve VO2peak, cardiac function, and blood pressure (Aamot et al., 2014). However, best measurement approaches to improve the aforementioned biomarkers remain equivocal. Aamot et al. (2014) examined RPE and its relationship to exercise intensity, as measured directly through a heart rate monitor. The authors discovered that the subjects’ RPE commensurate to approximately 85% of maximum heart rate was consistently lower when compared to achieving 85% maximum heart rate through direct measurement, by a heart rate monitor (Aamot et al., 2014). Although subjects consistently under-estimated their actual exercise intensities, there is still merit to implementing RPE.

RPE remains a viable tool because of ease of use. RPE also allows clients to remain in control of the level of intensity they wish to experience. Most of the author’s clients are recovering from motor vehicle accidents, and tend to exude reluctance to push too hard for fear of re-injury. In the author’s opinion, allowing a degree of autonomy during client’s post-rehab program helps foster trust, respect, and compliance throughout training. Additionally, RPE can be used simultaneously with heart rate (HR) monitors, as a means of developing biofeedback; clients can make associations between RPE and actual HR. Such an approach allows a client to slowly develop the ability to train and increase heart rate over time, in a specific fashion, thereby improving cardiac function. RPE, as a stand-alone methodology, might not be as specific when increasing intensity, as compared to a HR monitor intervention. However, RPE does have merit during initial stages of cardiovascular conditioning, when intensity will be deliberately lower.

In conclusion, RPE does contain a degree of subjectivity when self-interpreting exertion, yet remains a viable tool for the author’s clientele because of accessibility, simplicity, and ease of use. Although clients may underscore their degree of actual intensity, as evidenced by the work of Aamot et al. (2014), RPE still allows an opportunity for clients to become directly engaged in their post-rehabilitation program, and at a pace and level of effort that is comfortable for them.

References

Aamot, I.L., Forbord, S.H., Karlsen, T., & Støylen, A. (2014). Does rating of perceived exertion result in target exercise intensity during interval training in cardiac rehabilitation? A study of the Borg scale versus a heart rate monitor. Journal of Science & Medicine in Sport, 17(5), 541-545.

ACSM (2015). ACSM current comment; Perceived exertion. Retrieved https://www.acsm.org/docs/current-comments/perceivedexertion.pdf

Roberg, R., & Landwehr, R. (2002). The surprising history of the “HRmax=220-age” equation. Journal of Exercise Physiology, 5(2), 1-10. Retrieved from http://www.cyclingfusion.com/pdf/220- Age-Origins-Problems.pdf

-Michael McIsaac