Client Details: This author’s client is a 27-year old male, Karate (black belt), and Brazilian Jiu Jitsu (BJJ) (purple belt) competitor. He sustained a motor vehicle accident, is currently avoiding competitions, and has restricted himself to solely instructing students due to pain and discomfort along his upper back and low back. Additionally, he scored 1/1 on shoulder mobility screen on the Functional Movement Screen, and <45 degrees on both left and right thoracic rotation.

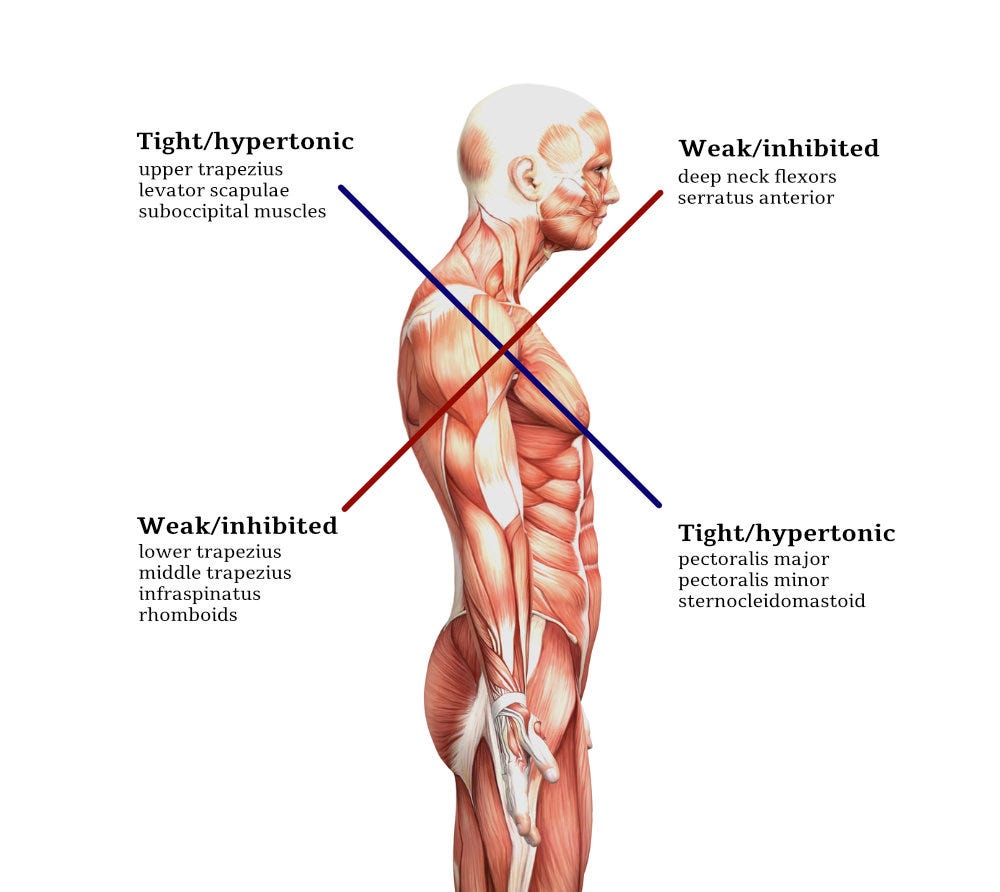

In this author’s last 3 posts, Vladimir Janda’s upper crossed syndrome (UCS) was explored, in addition to its relationship with the chronic musculoskeletal pain cycle (CMPC) (Page, Lardner, & Frank, 2010). Furthermore, stability and mobility restrictions, two central constituents of UCS, were covered as it related to the thoracic regions and scapular regions. Populations were identified that exhibited UCS and the relationship to seated and sedentary behavior. Finally, methods were presented to correct/reset the mobility restrictions within the thoracic spine, through self-myofascial release (SMR) techniques and thoracic mobility drills. In the following sections, this author will build upon all principles and methods discussed thus far, as a foundation to mitigate poorly stabilized upper extremities (i.e., scapulae) in the aforementioned client case.

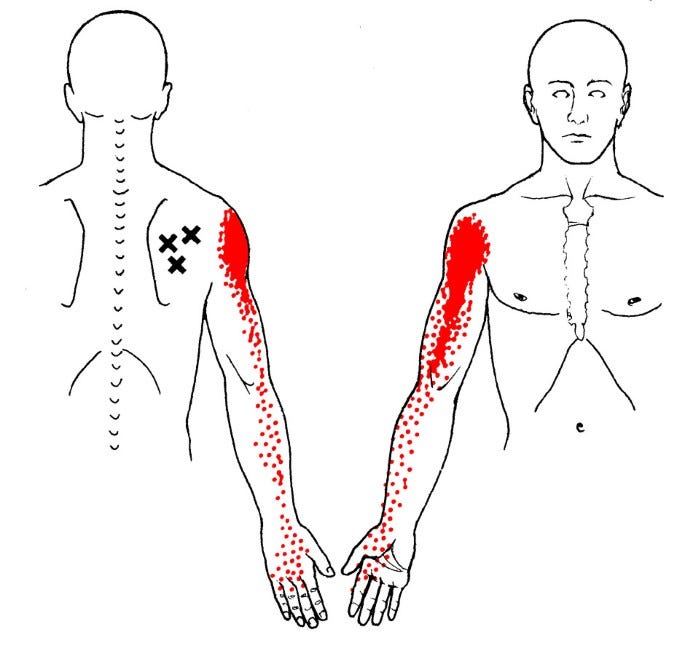

Poorly stabilized and painful shoulders are often associated with UCS, and exacerbated by thoracic hyperkyphosis (Page et al., 2010; Sahrmann, 2002). Thus, restoring range of motion (ROM) and function of the thoracic spine is paramount, and a pre-requisite to improving stabilization and rhythm of the scapulae. Cook (2016) stated that after a joint and surrounding musculature was placed back into an ideal position with no pain or restriction (i.e., reset), it was paramount to keep it from reverting back into the dysfunctional posture/movement pattern (i.e., reinforce). As trigger points (TPs) have been associated with causing pain and poor motor control, it is paramount to address such factors in the scapula (Bron, Dommerholt, Stegenga, Wensing, & Oostendorp, 2011). Such notions are reflected on page 376 table 32.1 by Liebenson (2014).

Davies and Davies (2013) on page 94 presented a chart outlining referral patterns from common TPs on the scapula. This author will often ask clients if there is discomfort along their arms (i.e., supraspinatus TP=discomfort medial shoulder, infraspinatus TP=discomfort anterior/medial shoulder and arm, teres minor TP=posterior shoulder joint) as a means of quickly identifying potential zones of pain (Davies & Davies, 2013). If TPs were present, this author would use a tennis ball to perform SMR. Pages 109, 112, and 118 of Davies and Davies (2013) outline how to use the tennis ball on the aforementioned rotator cuffs.

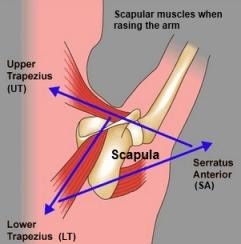

Following SMR of the rotator cuffs (if TPs are present) and thoracic spine (covered in previous posts), this author would implement postures and exercises to help keep the scapulae in advantageous biomechanics positions. Liebenson (2014) noted that development of the shoulder should first focus upon the intrinsic needs of the scapula: stability, flexibility, balance, strength, and endurance. Thus, exercises chosen should reflect such goals as a means of developing proximal stability, or a strong base, for the glenohumeral joint and arm to move upon (Liebenson, 2014).

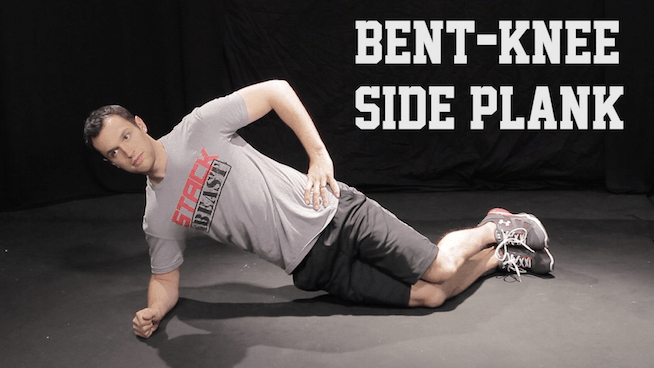

Table 32.1 on page 376 by Liebenson (2014) noted that coaching scapular retraction or depression, also known as packed shoulders, in conjunction with loosening facilitated muscles from UCS, is paramount. Furthermore, closed chain exercises (those in which the terminal segment moves very little, or is fixed) are preferred as they are simpler to learn, place less stress on the scapula and glenohumeral joint, and teach static stability of the scapula before dynamic stability (Liebenson, 2014). Finally, the scapula is found along a kinetic chain; it coordinates closely with a stiff core to transmit force, and act as a stable base, for the arm to move upon. Thus, closed chain exercises, which teach a statically stable scapula, should also include and incorporate a stable and statically positioned core. Liebenson (2014) proposed a side plank from the knees, as seen in figure 32-1, to capture and incorporate the aforementioned principles. Coaching cues to set the client in the appropriate position would include pulling the chin into the neck, extending the chest out slightly, and “pulling” the posted elbow under the body (i.e., external cues). External attentional focus has generally been found to be more effective and faster than internal attentional focus for acquiring and implementing a correct movement pattern (McNevin, Wulf, & Carlson, 2000).

Once the client can perform modified side planks pain-free, correctly, and with no coaching (i.e., phase 1 = weeks 1-3) phase 1 could continue in which exercises incorporate motions (i.e., dynamic) from the rest of the body, while continuing to implement a packed scapula. Illustration 32-5 on page 377 implements such methods through the sternal lift (Liebenson, 2014). Here the client develops a hip hinge (i.e., deadlift) while maintaining optimally positioned shoulders (i.e., retracted and depressed). A simple coaching cue would be to pull the chin into the neck, stick the chest out slightly, and drive the hips backwards (i.e., external cues).

Once the client can demonstrate the sternal lift optimally, without coaching, and is pain free, this author would introduce the low row. The low row, which builds upon the 2 aforementioned corrective exercises, can be seen in figure 32-8, page 378 (Liebenson, 2014). Here, the client would introduce slight arm motions (i.e., dynamic stability) built upon a packed scapula and properly engaged core (i.e., 3 kinetic chains working in sequence). The low row would represent the beginning of higher rotator cuff recruitment, while still maintaining a relatively statically stabilized scapula (Liebenson, 2014). Simple coaching cues would include pulling the chin into the neck, chest out slightly, while driving the hand “through” the edge of the table for 5-second holds (Liebenson, 2014).

In principle, this author agrees with the progressions of Liebenson (2014), although methods may vary. In essence, this author agrees with the following principles:

- Control pain (medical professional intervention before seeing an exercise professional)

- Mobility to stability (manual techniques-Registered Massage Therapist and/or SMR to stretches to side planks + progressions)

- Supine/prone/ground to standing (modified side plank to sternal lift to low row)

- Static to dynamic motions (modified side plank to sternal lift to low row)

- Simple to complex motions (modified side plank to sternal lift to low row)

- Proximal to distal (core stability to scapular stability to glenohumeral stability)

- De-loaded to loaded motions (SMR to flexibility to modified side planks to sternal lifts to low rows)

- Exercise progressions (corrective to strength to power to sport-specific skills)

- Determining progressions (decision to progress is based on pain-free status and ability to perform movement competently by the client)

In conclusion, this author would agree in the pragmatic and multidisciplinary approach that Liebenson (2014) implemented. It is essential to draw upon all specialists’ (i.e., physical therapists, athletic therapists, chiropractors, manual therapists, exercise professionals) expertise. This author would also agree with the other principles of Liebenson (2014) as outlined in the previous sections. Such principles provide a fertile environment, as well as a set of “checks and balances” for steady and consistent growth from an injured state, back to a return to play/activities of daily living.

References

Bron, C., Dommerholt, J., Stegenga, Wensing, M., & Oostendorp, R.A.B., (2011). High prevalence of shoulder girdle muscles with myofascial trigger points in patients with shoulder pain. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 12, 139.

Cook, G. (2016). The Three Rs. Retrieved from http://graycook.com/?p=1553

Davies, C., & Davies, A. (2013). The trigger point therapy workbook: Your self-treatment guide for pain relief(3rded.). Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Liebenson, C. (2014). Functional training handbook. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer.

McNivin, N.H., Wulf, G., & Carlson, C. (2000). Effects of attentional focus, self-control, and dyad training on motor learning: Implications for physical rehabilitation. Physical Therapy, 80(4), 373-385.

Page, P., Lardner, R., & Frank, C. (2010). Assessment and treatment of muscle imbalances: The Janda approach.Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Sahrmann, S. (2002). Diagnosis and treatment of movement impairment syndromes(1rst ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Inc.

-Michael McIsaac