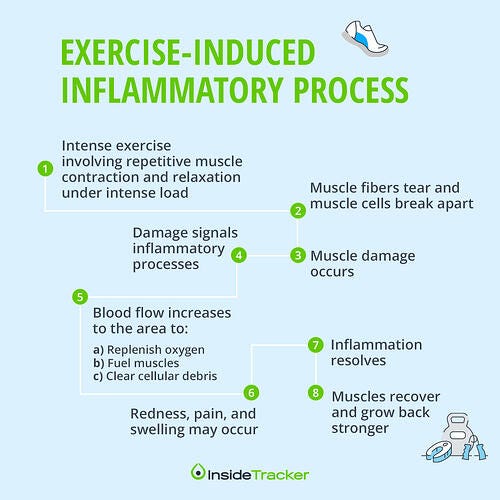

In my last post, characteristics of exercise-induced inflammation (EII) were explored. Topics included how brief and moderately intense exercise initiated an immune response, as well as the central physiological and biochemical processes required to achieve adaptation to the same stimuli of equal magnitude. In the following sections, food-induced inflammation (FII) will be reviewed, as well as the differences between the origins of inflammation (i.e., exercise-induced vs. food-induced) and the comparative long-term effects of both.

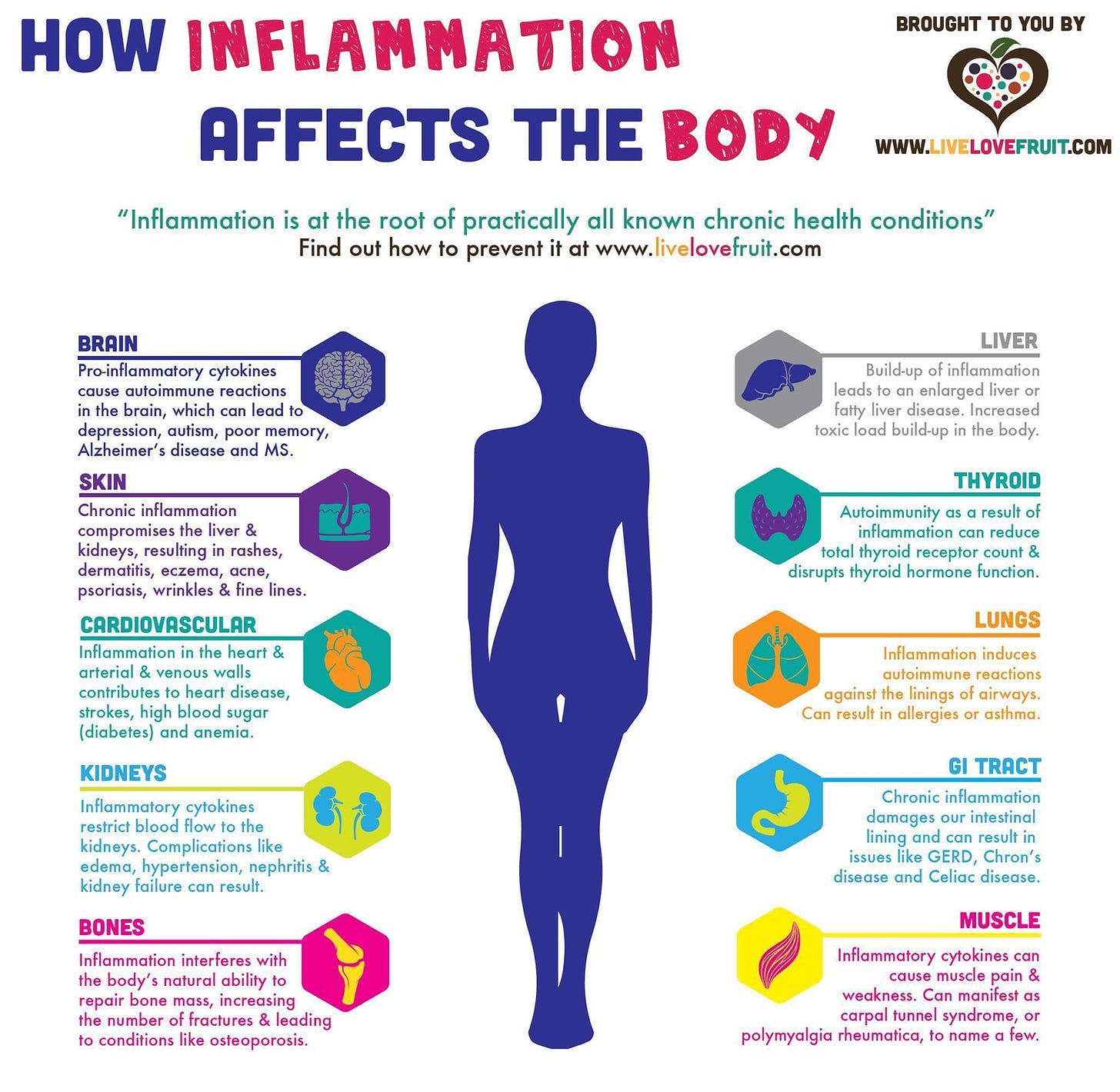

Inflammation is a natural immune response to neutralize and clear foreign bodies and damaged cells in a biological organism (Ilich, Kelly, Kim, & Spicer, 2014). The immune response can have several etiologies such as overconsumption of omega-6 rich foods, food sensitivities, poor sleep, stress, toxic environments, and intense physical activity (Ruiz-Nunez, Pruimboom, Dijck-Brouwer, & Muskiet, 2013). The optimal balance of conditions to develop an adaptation to a stressor, which improves health and performance, is known as hormesis (Radak, Chung, Koltai, Taylor, & Goto, 2008).

A key difference separating FII from EII is the incidence of exposure to stimuli; exercise is often brief and infrequent. However, inflammatory foods are generally consumed frequently and in large amounts, contributing to low-grade chronic inflammation and metabolic syndrome (Ilich et al., 2014). When viewing adaptation as a biochemical/physiological event that occurs from the minimally required stimulus (i.e., hormesis), chronic consumption of inflammatory foods surpasses that which is required to achieve hormesis.

However, it may be a viable option to expose an individual to inflammatory foods immediately after exercise, as a means of using the inflammatory response to expedite adaptation from exercise (Stell, 2015). Caution should be used, however, when implementing inflammatory foods to the general population.

Modern diets tend to include over 70% of total energy from refined sugars, refined vegetable oils, processed foods, and alcohol (Ilich et al., 2014). Of particular interest is the shift in polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) ratios circa early to mid nineteenth century, after the inclusion of grain in animal diets and the development of processed foods. Such a change increased the prevalence of omega-6 fatty acids in both meat and packaged food products (Ilich et al., 2014).

Since then, PUFA ratios between omega-6 and omega-3 have shifted from 1-2:1 to as high as 15:1 in modern diets, respectively, inducing low-grade chronic inflammation (Ilich et al., 2014). The aforementioned change in PUFA ratios has been linked to several chronic diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, atherosclerosis, and dyslipidemia (Ruiz-Nunez et al., 2013). Thus, it could be argued that although there may be a reason and opportunity to provide a pro-inflammatory food to individuals immediately after exercise, a stronger possibility exists that most of the population are already receiving excessive levels of pro-inflammatory diets.

In conclusion, a brief period of stressors inducing hormesis provides a meaningful opportunity for adaptation. However, as evidenced by trends in Westernized populations, most individuals are already consuming excessive levels of pro-inflammatory foods beyond that which is required to reach hormesis (Ruiz-Nunez et al., 2013). Thus, encouraging individuals to add more inflammatory nutrients may be short sighted. Instead, it may prove more appropriate to reduce the aforementioned foods to attenuate an already excessive immune response, thereby reaching homeostasis, health, and longevity in a more efficacious manner.

References

Ilich, J.Z., Kelly, O.J., Kim, Y., & Spicer, M.T. (2014). Low-grade chronic inflammation perpetuated by modern diet as a promoter of obesity and osteoporosis. Archives of Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology, 65(2), 139-148.

Radak, Z., Chung, H.Y., Koltai, E., Taylor, A.W., & Goto, S. (2008). Exercise, oxidative stress, and hormesis. Aging Research Reviews, 7(1), 34-42.

Ruiz-Nunez, B., Pruimboom, L., Dijck-Brouwer, D.A., & Muskiet, F. (2013). Lifestyle and nutritional imbalances associated with Western diseases: Causes and consequences of chronic systemic low-grade inflammation in an evolutionary context. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 24(7), 1183-1201.

Stell, B. (2015). Hormesis: When exercise-induced inflammation is beneficial. Retrieved from https://mycourses9.atsu.edu/webapps/discussionboard/do/message?action=list_messages&forum_id=_49629_1&nav=discussion_board&conf_id=_14850_1&course_id=_13345_1&message_id=_1193427_1#msg__1193427_1Id

-Michael McIsaac