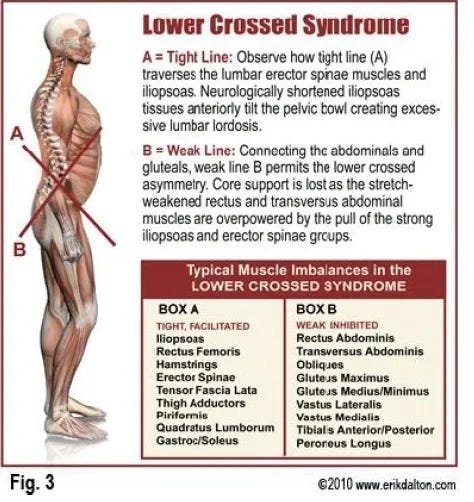

As was described previously in this author’s posts, lower crossed syndrome (LCS) is characterized by inhibited abdominals of the anterior side, in conjunction with the gluteus maximus/minimus/medius on the posterior side of the body. The rectus femoris and psoas major of the anterior side, in conjunction with the thoraco-lumbar extensors of the posterior side, have a tendency to be overactive/facilitated (Page, Lardner, & Frank, 2010). Such imbalances drive the hip joint/pelvis into an anterior tilt, causing a hyperlordic curve in the lumbar vertebrae with an associated extended abdomen (Sahrmann, 2002). The individual may also present with low back pain; symptoms may increase when reaching overhead, standing, or lying supine with the legs extended (Sahrmann, 2002). Finally, as it relates to the scope of this post, aberrant movement patterns within the hip complex (specifically gluteus medius) have been associated with knee instability, and patellofemoral pain (PFP) (Kim, Unger, Lanovaz, & Oates, 2016).

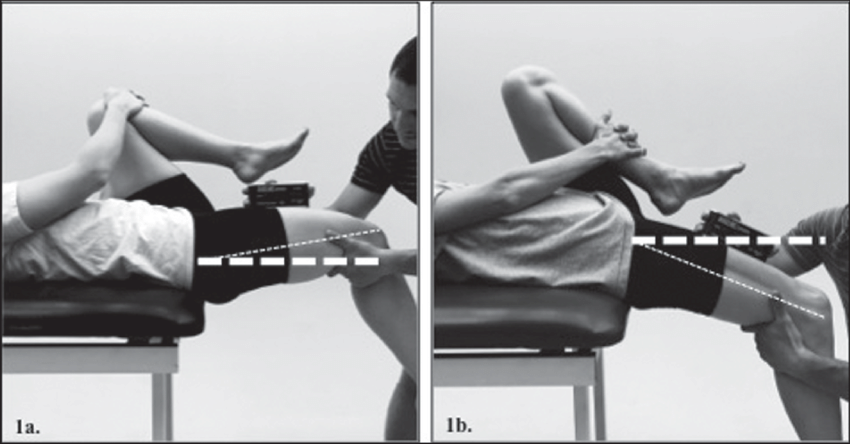

Prior to implementing exercise to correct onset and magnitude of gluteus medius activation, hip extension should be screened by implementing the modified Thomas test (MTT). Details of the aforementioned test have been described in this author’s previous posts. Normal resting hip extension in a supine position is 0°, indicated by the femur resting along the table. Normal resting length of the rectus femoris allows the knee to remain at 90° knee flexion. Deviations (i.e., hip resting above the table, or the knee less than 90° flexion) indicate facilitated/short psoas and rectus femoris muscles (Page et al., 2010). Such information is important as facilitated hip flexors can affect the degree of recruitment, and timing of, the gluteus muscles. The aforementioned phenomenon is also known as reciprocal inhibition (Page et al., 2010).

Following the mitigation of trigger points (TPs), if present, and lengthening of facilitated hip flexors (i.e., minimizing muscular discomfort, restoring normal range, and joint position) would be the reinforcement phase of Cook (2016). Here, exercises would be chosen to improve the timing and magnitude of muscle recruited in the lateral hip regions, both of which are considered central to lower extremity control (Kim et al., 2016). Finally, exercises that lengthen muscle/increase joint range of motion (i.e., mobility) will be combined with exercises that increase motor control (i.e., stability), as the aforementioned methods are mutually inclusive.

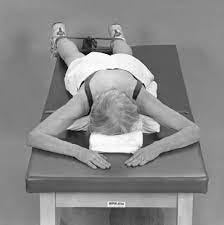

Prone unilateral hip extension (PUHE) is an exercise, which has been shown to recruit and activate the gluteus musculature (Sahrmann, 2002). Furthermore, the exercise minimizes the degrees of freedom (number of joints and muscles in a movement pattern, and the motions created) and complexity of motion, thus allowing the individual to focus exclusively upon activation of the hip extensors (Magill, 2011). Sahrmann (2002) recommended holding each repetition for 3-10 seconds.

A second progression would include prone unilateral hip extension with knee extension (PUHEKE) (Sahrmann, 2002). Here, the client extends the hip while simultaneously maintaining an extended knee. The rationale is to help foster optimal timing and synergistic assistance of the hamstrings during hip extension. Sahrmann (2002) recommended holding each repetition for 3-10 seconds.

A third progression would include prone unilateral hip extension plus abduction (PUHEA). As the client becomes comfortable with PUHE and PUHEKE (i.e., is pain free and performs the motion without this author’s coaching), PUHEA is introduced. Here, the client extends the hip with abduction. Such a progression from PUHE/PUHEKE to PUHEA is subtle, allowing the individual to acquire the appropriate motor skills without overburdening him/her with excessive/premature complexity of motion. Additionally, Suehiro et al. (2014) noted that prone extension with abduction had higher hip extensor activity, while lowering hamstring activity, compared to hip extension without abduction. Sahrmann (2002) recommended each repetition last 3-10 seconds.

A fourth progression would include supine hip extension (single or double leg) with the knees flexed (i.e., glute bridges). Such an exercise is important because it is closed kinetic chain (i.e., the distal limb is fixed); a position in which the hips are often exposed to and must competently interface with (i.e., standing, lifting, squatting, planting the foot while climbing stairs). Secondly, such a position includes interaction of the foot to the ground. Foot/ground contact is essential in knee and hip control because it provides considerable afferent feedback, helping determine lower extremity control during exercise and motion (Page et al., 2010).

Developing hip/pelvic stability and timing/magnitude of gluteus medius and maximus activity is key to improving lower extremity biomechanics and movement quality. Implementing motions that target the aforementioned regions should also abide by basic motor learning principles; clients should be systematically exposed to exercises (pain free), which slowly increase the degrees of freedom. Such an approach allows time and opportunity for clients to acquire basic motor skills before exposure to more complex motions. Finally, fusion of physiological and motor learning principles allows for cautious, yet progressive, methods to achieve optimal movement, pain-free status, and an expedited return to activities of daily living.

References

Cook, G. (2016). The Three Rs. Retrieved from http://graycook.com/?p=1553

Kim, D., Unger, J., Lanovaz, J.L., & Oates, A.R. (2016). The relationship of anticipatory gluteus medius activity to pelvic and knee stability in the transition to single leg stance. American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 8(2), 138-144.

Magill, R. A. (2011). Motor learning and control: Concepts and applications (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Page, P., Lardner, R., & Frank, C. (2010). Assessment and treatment of muscle imbalances: The Janda approach.Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Sahrmann, S. (2002). Diagnosis and treatment of movement impairment syndromes(1rst ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Inc.

Suehiro, T., Mizutani, M, Okamoto, M., Ishida, H., Kobara, K., Fujita,, D., … Watanabe, S. (2014), Influence of hipjoint position on muscle activity during prone hipextensionwith knee flexion. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 26(12), 1895-1898.

-Michael McIsaac