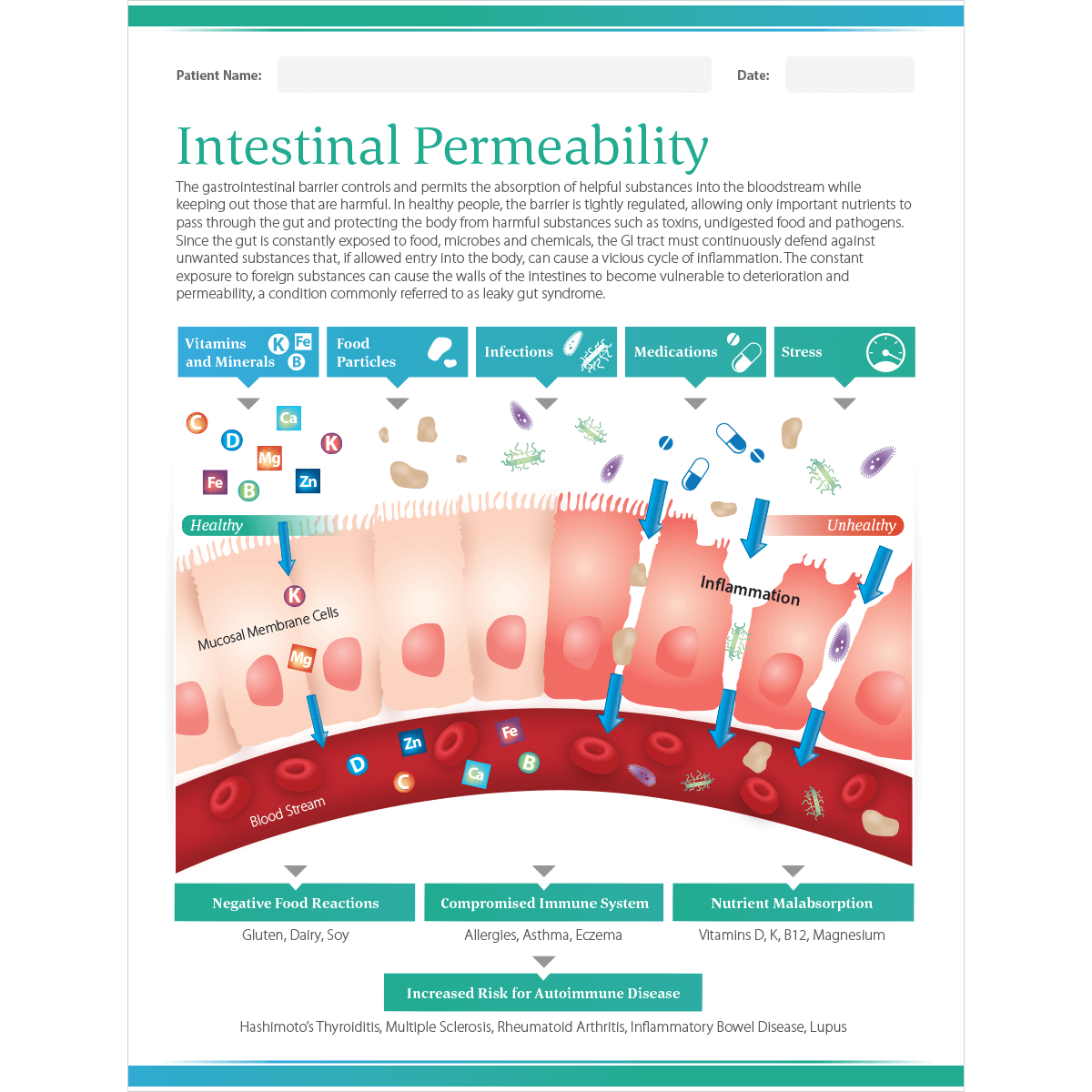

Increased intestinal permeability (IP) is correlated to several pathologies such as allergies, metabolic, and cardiovascular disturbances. As was discussed in previous posts, substances that are normally unable to cross the epithelial barrier gain access to the systemic circulation (i.e., leaky gut) (Rapin & Weirnsperger, 2010). One particular cause of leaky gut is processed food consumption, and one nutrient that can rectify IP is glutamine (Rapin & Weirnsperger, 2010). As a means of appreciating nutritional interventions that correct IP, the following will consider processed food consumption more deeply, in addition to its relationship to gut function and glutamine.

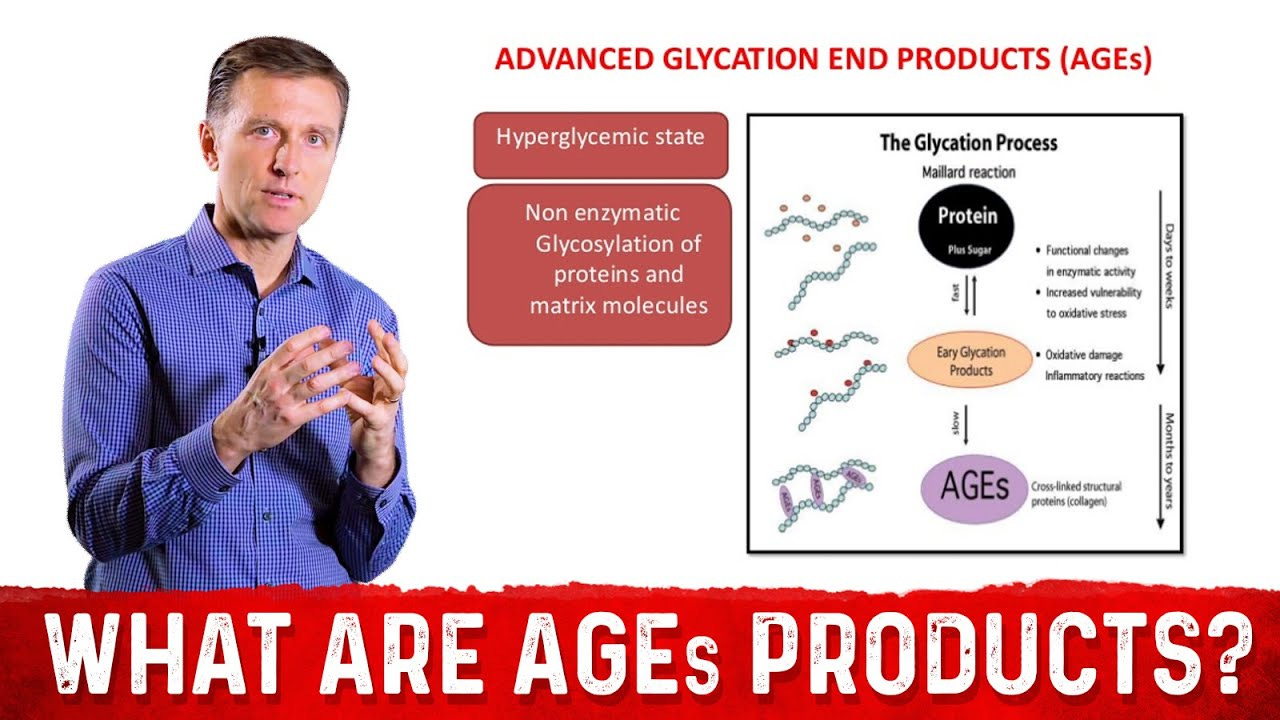

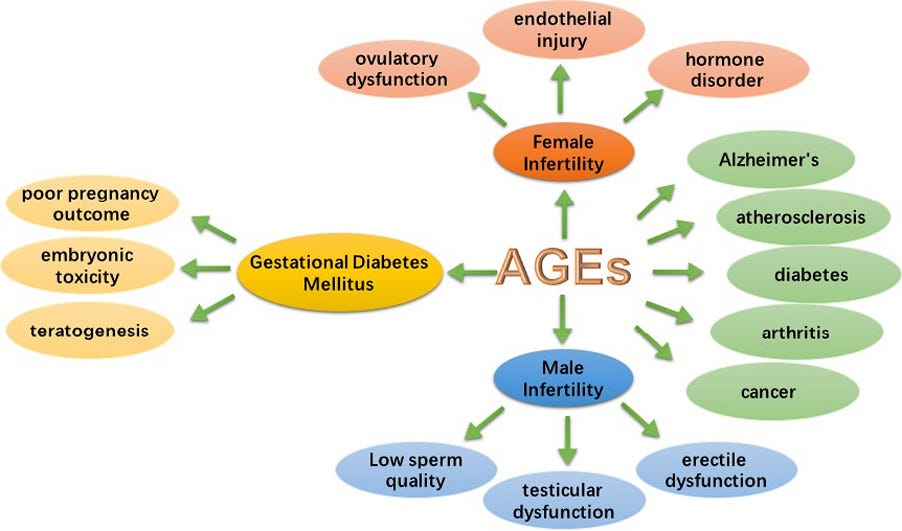

Processed foods harbor a substance known as advanced glycation end products (AGEs), and it arises from the fusion of high temperatures (i.e., frying and broiling), flavoring, and increased use of sugars (Rapin & Weirnsperger, 2010). AGEs are also found in beverages such as tea, coffee, diet coke, and soy sauce, and they are the final product of several reactions whereby sugars spontaneously react with molecules such as aminopeptides, lipids, and nucleic acids. Ultimately, AGEs produce free radicals in the human body; a process that has the potential to induce to systemic inflammation, if IP is also present (Rapin & Weirnsperger, 2010).

Rapin and Weirnsperger (2010) stated that AGEs generally do not have deleterious effects on a properly functioning gastrointestinal tract (GIT). In a normally functioning GIT, AGEs enter the intestine, but are poorly absorbed. However, AGEs that do make it into the bloodstream are quickly removed by hepatic processes and endothelial cells (Rapin & Weirnsperger, 2010). The challenge to homeostasis arises when IP is present and exposed to AGEs. The following will consider such manifestations.

If IP and AGEs co-exist, it is thought to contribute to two pathological situations: allergies and metabolic disorders. The researchers cited a study whereby immunosuppressive drugs (tacrolimus) were used to induce IP; such immune-compromised conditions lead to more food allergies (Rapin & Weirnsperger, 2010). Additionally, when the gut lining was directly exposed to AGEs (methylglyoxal or glyoxal), inflammatory responses increased dramatically.

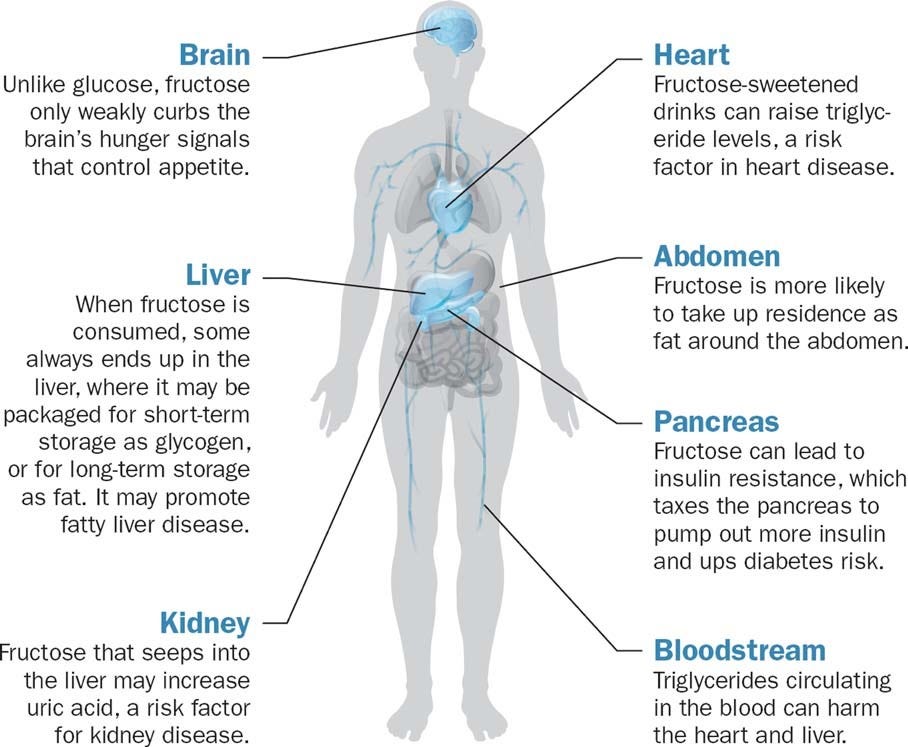

Metabolic derangement has also been linked to another AGE; fructose. Rapin and Weirnsperger (2010) noted that fructose consumption has been correlated directly with worldwide obesity. Another study indicated that high intake of fructose was associated with glucose intolerance in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (related to intestinal permeability). Said study also indicated that approximately one-third of patients presented with fructose intolerance, suggesting a possible connection to AGEs (Rapin & Weirnsperger, 2010). Having explored the connection to IP and AGEs, the following will consider glutamine and its relationship to IP.

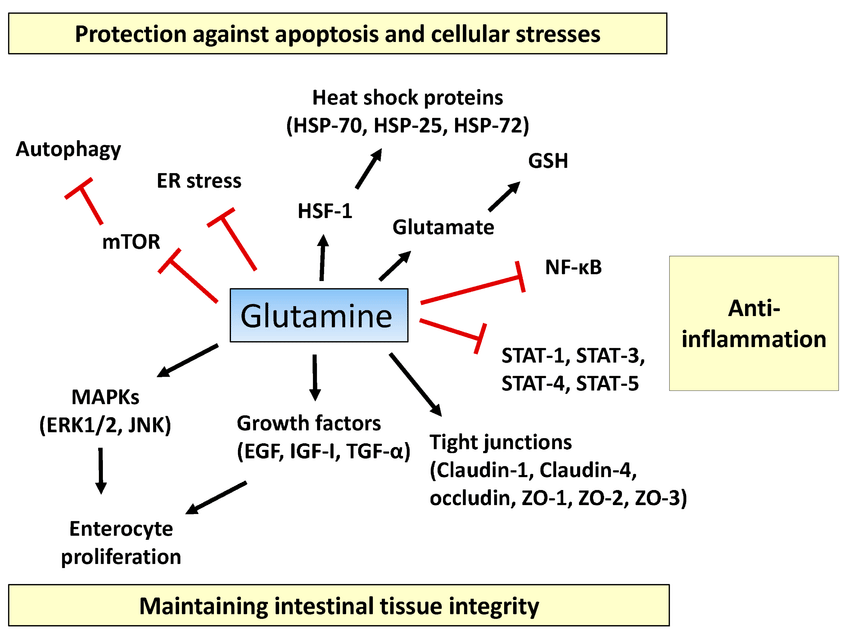

Glutamine is one, of many, nutrients shown to help rectify IP. Glutamine is the preferred substrate for enterocytes (cells in the intestinal lining), and works in with other amino acids, such as leucine and arginine, to maintain gut integrity and function (Rapin & Weirnsperger, 2010). Such evidence helps explain why glutamine (in intestinal cell cultures) was shown to maintain transepithelial resistance. In mal-nourished children, intestinal barrier function was also improved via glutamine supplementation. Finally, allergies were controlled in low birth-weight children by ingesting glutamine (Rapin & Weirnsperger, 2010).

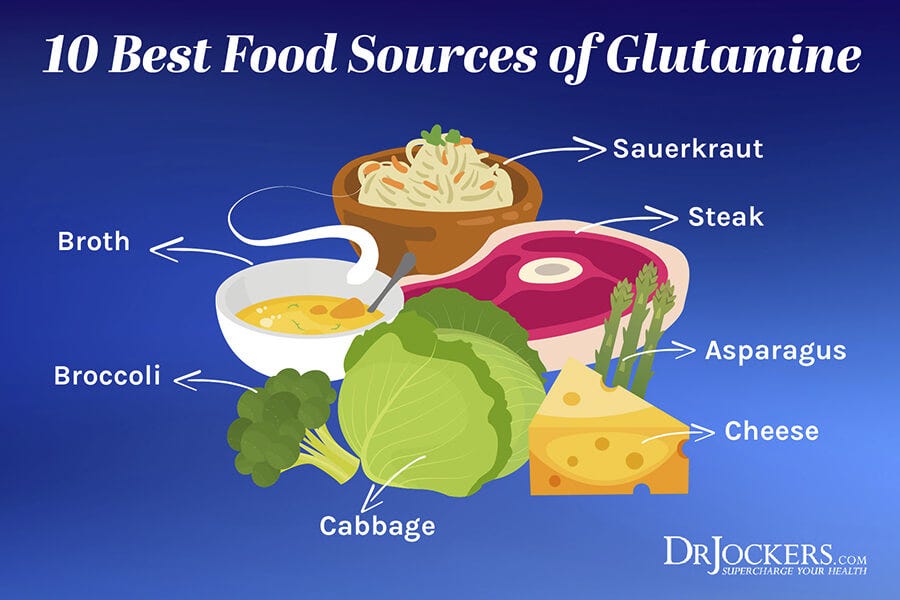

In conclusion, IP and AGEs can negatively affect homeostasis, especially when combined. Simple strategies to help control gut-related maladies could include abstinence from processed foods (which contain AGEs) and the introduction of glutamine in the diet. Such simple interventions are likely to attenuate gut permeability thereby optimizing health, longevity, and quality of life in those afflicted with IP.

References

Rapin, J. R., & Weirnsperger, N. (2010). Possible links between intestinal permeability and food processing: a potential therapeutic niche for glutamine. Clinics, 65(6), 635-643.

-Michael McIsaac