Most activities that individuals experience occur predominantly on one leg such as walking, climbing stairs, and changing direction (McCurdy, O’Kelley, Kutz, Langford, Ernest, & Torres, 2010). Considering this to be true, it would stand to reason exercise professionals acknowledge this when considering specificity of training. Pertinent questions should arise from this: if we are generally moving on one leg, should we train on one leg? If so, why?

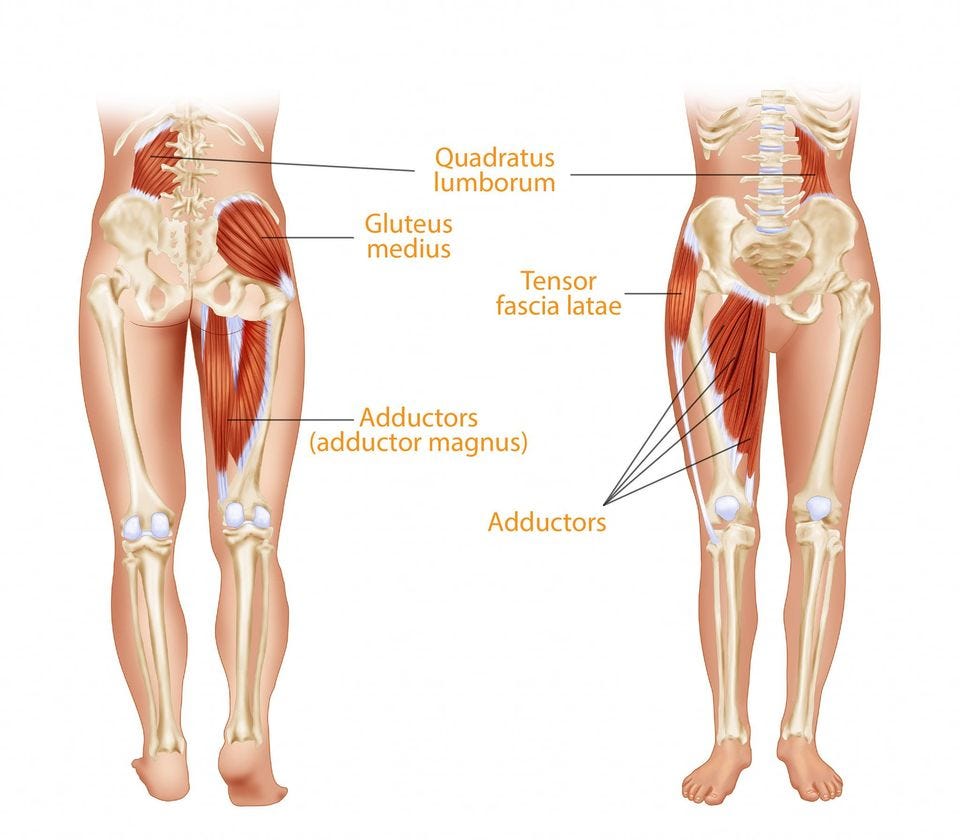

When training any movement pattern, the more muscle activity involved, the more force and stability that can be produced. McCurdy et al. (2010) discovered that there was higher EMG activity in the gluteus medius and hamstring musculature in a single leg squat when compared to a bilateral squat. This has value because the gluteus medius helps the gluteus maximus control femoral internal rotation, a common movement dysfunction that arises from poorly stabilized hips (Bliven, 2014).

Another reason to target single leg exercises arises from a group of muscles that help control the knee and hips; the lateral subsystem. This system is composed of the same-side adductor magnus, gluteus medius and contralateral quadratus lumborum (Clark, Lucett, & Kirkendall, 2010). These muscles help control both the hip and knee in the frontal plane while in a single leg stance. If this system is working in a dysfunctional fashion, femoral internal rotation and adduction of the same hip can occur. This equates to a poorly stabilized patellofemoral joint. This helps support the notion of training in a single leg fashion to access this muscular subsystem. Below are examples of terminal exercises that I use in my practice to stimulate and develop this system. It should be noted that clients are slowly progressed to these exercises:

Single Legged Deadlift

Rear Foot Elevated Split Squats

Knee stabilization requires several muscles working in a clear and coordinated fashion. Understanding the functional anatomy and pathomechanics of the knee is paramount, as it allows us to recruit the dynamic stabilizers in a meaningful and efficacious way.

References

Bliven, K. (2014). Functional anatomy of the knee. Part 1: Anatomy [Slideshow Presentation]. Retrieved February 17, 2014, from http://assets.atsu.edu/BB/ASHS/HM/HM502/HipThightP1.mp4

Clark, M., Lucett, S., & Kirkendall, D.T. (2010). NASM’s essentials of sports performance training. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

McCurdy, K., O’Kelley, E., Kutz, M., Langford, G., Ernest, J., & Torres, M. (2010). Comparison of lower extremity EMGbetween the 2-legsquat and modifiedsingle-legsquat in female athletes. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation. 19 (1), 57-70.

Comparison of lower extremity EMGbetween the 2-legsquat and modified single-legsquat in female athletes

-Michael McIsaac