Clients recovering from motor vehicle injuries that are ready and approved for strength training (i.e., post-rehabilitation) require well-developed programs, which maximize effectiveness while minimizing risk of re-injury. Extensive weakness and deconditioning are common traits among the aforementioned populace, dominated by middle-aged (40-65 years) clientele in the author’s practice. Clients are often seeing a medical professional (i.e., Physiotherapist, Chiropractor, Family Physician), or have been recently discharged. Their injuries are usually resolved, but they are often weak and unready for the rigors of daily activity or work-related tasks.

Thus, margin of error is small and risk of re-injury is high, requiring training programs deeply imbedded in pragmatic and evidence-based approaches. Skill acquisition requires time, problem solving, and refinement of movement; such a process must be accompanied by a method that reduces the exposure to undesirable movement patterns that may exacerbate injured regions. Most post-rehabilitation (PR) clients have little-to-no exercise experience, demanding that movements are gentle, concise, and yet progressive in nature to yield improvements in mobility, stability, and strength over time. In the following sections, the author would like to present a corrective/strength-training program designed for a PR client recovering from a low-back injury, as a means of exploring and implementing the constituents of an evidence-based approach and best practice.

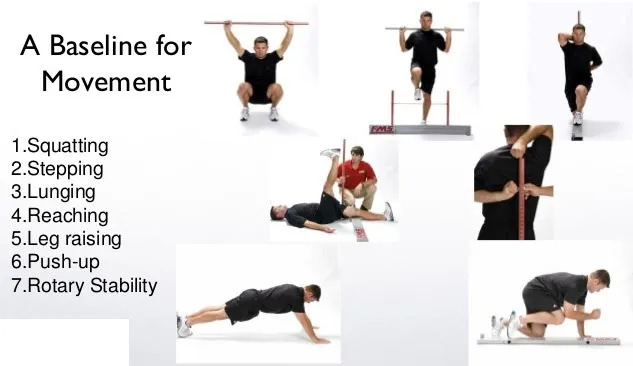

PR clients must regain pain-free range of motion, and have written approval to engage in a strengthening program, before seeing the author for strength training. Furthermore, the client must complete a deeper screening by the author via medical questionnaires, movement screens, and blood pressure readings (MRM Kinetics, 2015). In addition to stabilizing and strengthening the previously injured region, the terminal goal of the client’s program is to improve the strength and quality of functional/everyday motions: pushing, pulling, squatting, lifting, carrying and locomotion.

A key step in the client’s PR program is to integrate his/her injured regions back into the aforementioned functional/everyday patterns. To that end, the client’s program will reflect the aforementioned goals. The following sections will explore two key concepts in the development of a PR program for low-back injuries; dynamic pattern theory and the F.I.T.T. (i.e., frequency, intensity, time, type) principle.

Developing an 8-week low-back PR program requires an evidence-based and periodized plan. Everyday functional motions (i.e., pushing, pulling, squatting, lifting, carrying, and locomotion) are complex, multi-joint endeavors whereby the body develops strategies for controlling movement in a coordinated and harmonious fashion. Magill (2011) refers to this as the degrees of freedom problem. However, low-back clients often suffer losses in motor control, in which perturbed motor patterns emerge (Hodges and Richardson, 1999).

Such losses in spinal stability may further exacerbate symptoms in an already injured low-back (Hodges and Richardson, 1999). Thus, program design must address the aforementioned motor pattern deficits before strength training can occur, as a means of avoiding the placement of unnecessary loads through an unstable spine (McGill, 2007). Having briefly considered motor control and its placement in a low-back PR program, the following sections will review the F.I.T.T. principle, and its application to developing a periodized low-back stabilization and strengthening program.

F.I.T.T. (Intensity)

Intensity of exercise is generally determined as a percentage of 1RM (repetition maximum) (Garber et al., 2011). As the author’s clientele are recovering from injuries, determining percentages of 1RMs would likely be contraindicated, as PR clients recovering from low-back injuries generally have decreased tolerances to high force outputs (McGill & Karpowicz, 2009). During initial stages, the author will choose repetitions that are higher, as a means of helping guarantee that loads are lower (i.e., 10-15 repetitions), including 2-4 sets per exercise, which are also appropriate for the author’s middle-aged (40-65 years) population (Garber et al., 2011). Additionally, isometric core exercises (i.e., front and side planks) will be held for time over 2-4 sets culminating to approximately 147 seconds and 85 seconds, respectively. The aforementioned times were endurance averages obtained from healthy male and female subjects who held neutral, isometric positions in the frontal and sagittal planes (McGill, Childs, & Liebenson, 1999).

F.I.T.T. (Frequency and Time)

The author’s clientele are recommended to engage in full body exercise 2-3 times per week (Garber et al., 2011). In the initial stages of PR, clients are generally encouraged to train on alternating days to allow for adequate recovery between sessions (i.e., Monday, Wednesday, Friday), which is also congruent with the aforementioned training frequencies of Garber et al. (2011).

F.I.T.T. (Type)

There are two distinct phases in the author’s PR programs: a corrective exercise phase and a strengthening phase. Corrective exercise may be defined as exercise designed to maintain full joint mobility, improve flexibility, and strengthen/stabilize weakened muscles (Therapeutic Exercise, 2015). Strength, or force production, is improved by increasing the number of myosin cross bridges attached to actin filaments (Baechle & Earle, 2000). Two mechanisms that have been shown to increase force production are: frequency of stimulation of motor units, and the number of motor units recruited (Baechle & Earle, 2000). More detailed explanations of corrective/strength exercises and progressions will be covered in the following sections.

WEEK: #1 and #2 (Performed Three Days- Monday, Wednesday, Friday)

| Exercise | Purpose | Sets | Reps/Duration | Resistance | Comments |

| Self-Myofascial Release | Warm-Up | 1 | 10 | Bodyweight | Focus is on all major muscle groups: calves, front thighs, hamstrings, hips, low back, upper back, with particular emphasis on hip flexors* |

| Static Stretching | Warm-Up | 1 | 30-60 seconds | Mild | Focus on all restricted muscles, with particular focus on hip flexors |

| Dead Bug | Corrective/Stabilization | 1-2 | 7-8 second holds x 6-8 repetitions** | Body Weight | Have client hold the dead-bug at the end range |

| Bird Dog | Corrective/Stabilization | 1-2 | 7-8 second holds x 6-8 repetitions** | Body Weight | Have client hold the bird-dog at the end range |

** Holding each repetition for 7-8 seconds is recommended to build endurance, while also circumventing ischemic events in the target muscles (McGill, 2007).

A prevalent condition in North American populations is lower crossed syndrome (LCS) (Page, Frank, & Lardner, 2014). LCS is characterized by an inhibition of the abdominals and the gluteus minimus/maximus/medius. Conversely, the rectus femoris/iliopsoas of the anterior side and thoraco-lumbar extensors of the posterior side tend to be overactive/facilitated. Thus, a crossed pattern of inhibited and facilitated muscles exists (Page et al., 2014). The condition can find most of its dysfunction from the hip flexor regions; if hip flexors are short or tight, hamstrings become lengthened creating a posterior tilt when deadlifting objects. Such an aberrant movement pattern forces the lower spine into flexion; a position which can cause disc failure in the low-back (McGill, 2007). Thus, stretching the hip flexors, if LCS is present, is undertaken before stabilization or strengthening exercises. Additionally, self-myofascial release (SMR) has been shown to loosen muscles without losses in force production and strength (Sullivan, Silvey, Button, & Behm, 2013). As evidence supports the efficacy of each modality, the author combines both; Mohr, Long, and Goad (2014) suggested that fusing modalities (i.e., SMR and static stretching) maximized muscle tissue length changes more than one approach in isolation.

Weeks 1 and 2 also include two rudimentary exercises: the dead-bug and bird dog. Following mobilization exercises (i.e., SMR and static stretching) are movements that improve motor control. The intent of the aforementioned exercises is to improve smooth motions of the arms and legs, while leaving the back in a neutral position. Since chronic low-back motions (compression, rotation, flexion, extension) can irritate the discs and nerve roots, McGill (2007) submitted that prior to force production via strength training, correcting aberrant movement patterns is paramount.

The bird-dog and dead-bug are also chosen as beginning exercises for specific reasons. Injured clients must learn fundamental movements that are used in work and daily activity such as lifting (i.e., deadlifting) while sparing low-back motions. The deadlift is a terminal exercise in the author’s PR program. However, the aforementioned exercise involves the body developing a strategy for controlling many joints (i.e., ankles, knees, hips, low-back, upper-back, shoulders, neck) in a coordinated and harmonious fashion. Magill (2011) refers to this as the degrees of freedom problem. Choosing the bird-dog and dead-bug, as beginning exercises, allows the body to control less joints (i.e., hip and shoulder motions) first before incorporating more joints (i.e., knees, ankles, elbows, upper back, neck), muscles, and movement patterns. Additionally, the dead-bug and bird-dog are chosen as beginning exercises, because they develop endurance of the core, which has been associated with healthy, stable backs (McGill, 2007). Holding each repetition for 7-8 seconds is recommended to build endurance, while also circumventing ischemic events in the target muscles (McGill, 2007).

WEEK: #3 and #4 (Performed Three Days- Monday, Wednesday, Friday)

| Exercise | Purpose | Sets | Reps/Duration | Resistance | Comments |

| Self-Myofascial Release | Warm-Up | 1 | 10 | Bodyweight | Focus is on all major muscle groups: calves, front thighs, hamstrings, hips, low back, upper back, with particular emphasis on hip flexors* |

| Static Stretching | Warm-Up | 1 | 30-60 seconds | Mild | Focus on all restricted muscles, with particular focus on hip flexors |

| Dead Bug | Corrective/Stabilization | 2-4 | 7-8 second holds x 6-8 repetitions | Body Weight | Have client hold the dead-bug at the end range |

| Bird Dog | Corrective/Stabilization | 2-4 | 7-8 second holds x 6-8 repetitions | Body Weight | Have client hold the bird-dog at the end range |

| Front Plank | Stabilization/Endurance(Sagittal Plane) | 1-2 | Up to 45 seconds | Body Weight | Start motion 4 feet off off the ground |

| Side Plank | Stabilization/Endurance(Frontal Plane) | 1-2 | Up to 45 seconds | Body Weight | Start motion 4 feet off of the ground |

Weeks 3 and 4 continue to include motions, which separate arm and leg movement from low-back movement while building muscular endurance (i.e., dead-bugs and bird-dogs). Exercises are added slowly every two weeks to allow the client to acclimate to desired volumes (i.e., 2-4 sets per exercise). McGill (2007) stated that volume and intensity with low back clients can vary from session to session, and that the aforementioned F.I.T.T. principles should accommodate the client’s capacity for exercise; if a client becomes tired or begins experiencing painful symptoms, allow rest and slowly build up during the next sessions.

After finer motor control is established through the dead-bug and bird dog, weeks 3 and 4 include additional motions that are chosen to further stabilize the low-back by inducing isometric contractions of the entire abdominal musculature (i.e., internal obliques, external obliques, rectus abdominis, transverse abdominis). Such isometric contractions create stiffness; a state that helps stabilize the lower spine in the presence of outside perturbations (i.e., lifting objects off of the floor) (McGill & Karpowicz, 2009).

Chronic motions in the frontal, sagittal, and transverse planes can cause tissue failure within the discs of the low-back (McGill, 2007). Thus, exercises are chosen to resist such motions. The bird-dog was responsible primarily to separate arm and leg movement from the low back (i.e., improving stability), in addition to building muscular endurance. However, the bird-dog also teaches the body to resist rotation; demanding level hips and upper back during the motion forces the body to resist twisting (i.e., transverse plane) (McGill & Karpowicz, 2009). Having addressed a means of resisting transverse motion of the low-back, front planks and side planks are implemented in weeks 3 and 4 to address resisting motion in the sagittal and frontal planes, respectively. Both exercises begin at a high angle relative to the floor (i.e., using risers and steppers to increase the angle). Such an approach attenuates the degree of force required to resist motions in the frontal (i.e., side planks) and sagittal (i.e., front planks) planes, thereby easing the client into holding the isometric contractions towards 45 seconds. As the client progresses through each week, the angle slowly lowers towards the floor until the client is performing the side and front plank with elbows on the ground.

WEEK: #5 and #6 (Performed Three Days- Monday, Wednesday, Friday)

| Exercise | Purpose | Sets | Reps/Duration | Resistance | Comments |

| Self-Myofascial Release | Warm-Up | 1 | 10 | Bodyweight | Focus is on all major muscle groups: calves, front thighs, hamstrings, hips, low back, upper back, with particular emphasis on hip flexors* |

| Static Stretching | Warm-Up | 1 | 30-60 seconds | Mild | Focus on all restricted muscles, with particular focus on hip flexors |

| Dead Bug | Corrective/Stabilization | 3-4 | 7-8 second holds x 6-8 repetitions | Body Weight | Have client hold the dead-bug at the end range |

| Bird Dog | Corrective/Stabilization | 3-4 | 7-8 second holds x 6-8 repetitions | Body Weight | Have client hold the bird-dog at the end range |

| Front Plank | Stabilization/Endurance(Sagittal Plane) | 2-4 | Up to 45 seconds | Body Weight | Start motion 1-2 feet off off the ground |

| Side Plank | Stabilization/Endurance(Frontal Plane) | 2-4 | Up to 45 seconds | Body Weight | Start motion 1-2 feet off of the ground |

| Deadlift Patterning | Strength | 1-2 | 10-15 | Bodyweight | Place knees against a bench, and place the entire spine against a dowel |

WEEK: #7 and #8 (Performed Three Days- Monday, Wednesday, Friday)

| Exercise | Purpose | Sets | Reps/Duration | Resistance | Comments |

| Self-Myofascial Release | Warm-Up | 1 | 10 | Bodyweight | Focus is on all major muscle groups: calves, front thighs, hamstrings, hips, low back, upper back, with particular emphasis on hip flexors* |

| Static Stretching | Warm-Up | 1 | 30-60 seconds | Mild | Focus on all restricted muscles, with particular focus on hip flexors |

| Dead Bug | Corrective/Stabilization | 3-4 | 7-8 second holds x 6-8 repetitions | Body Weight | Have client hold the dead-bug at the end range |

| Bird Dog | Corrective/Stabilization | 3-4 | 7-8 second holds x 6-8 repetitions | Body Weight | Have client hold the bird-dog at the end range |

| Front Plank | Stabilization/Endurance(Sagittal Plane) | 3-4 | Up to 45 seconds | Body Weight | Start motion on the ground |

| Side Plank | Stabilization/Endurance(Frontal Plane) | 3-4 | Up to 45 seconds | Body Weight | Start motion on the ground |

| Deadlift | Strength | 2-4 | 6-8 | Body Weight + External Loads | Continue to coach neutral spine |

Weeks 5 and 6 slowly increase total sets on each motor control (i.e., bird-dog and dead-bug) exercise to the target volume of 3-4 sets. Core stability/endurance exercises (i.e., front and side planks) are approximately between 2-4 sets, finally reaching target volumes of 3-4 sets in weeks 7 and 8. Weeks 5 and 6 are also characterized by inclusion of a lifting pattern, known as the deadlift.

Dynamic pattern theory posits that new movements can arise suddenly and abruptly over time. It also states that novel movements are governed by constraints, self-organization, patterns, and stability (Clark, 1995). In combination, these factors “steer” the development and refinement of movement and skills over time. As a means of managing the degrees of freedom problem, exercises are regressed in such a way as to allow the body to manage fewer joints, before including more joints (Magill, 2011). The deadlift is a functional exercise, as it teaches clients how to lift objects in a way that is spine conserving (McGill, 2007). However, there are also many joints, muscles, and movement patterns to manage (i.e., ankles, knees, hips, core, low back, upper back, neck). Thus, the author implements constraints to help decrease the number of joints the body must manage (Clark, 1995). Such a task is achieved by the use of a weight bench and broom handle. The broom is placed along the client’s entire spine, which helps provide feedback as to the neutrality of the back. The bench is placed along the client’s knees to encourage a posterior weight shift of the hips. Weeks 5 and 6 provide six opportunities (i.e., Monday, Wednesday, Friday x 2 weeks) to pattern the deadlift, before external loads are included in weeks 7 and 8.

In conclusion, weeks 1 to 8 represent the culmination of a periodized approach that addresses all critical stages of a low-back post-rehabilitation program; aberrant motor patterns are controlled (i.e., via the implementation of the dead-bug, bird-dog, and verbal coaching of a neutral spine), followed by exercises that brace the core and low-back in all three planes of motion (i.e., frontal, transverse, sagittal), finishing with a movement that demands full body coordination of all major muscles and joints, while integrating the core in a functional fashion (i.e., the deadlift) (McGill, 2007). Implementing the aforementioned approach allows the client an opportunity to slowly build stability, endurance, and full body strength while protecting the spine and improving performance. Such an evidence-based method, when fully embraced, helps maximize the client’s recovery, welfare, and quality of life while minimizing chances of re-injury and setback.

References

Baechle, T.R., & Earle, R.W. (2000). Essentials of strength and conditioning (2nd Ed.): National Strength and Conditioning Association. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Clark, J.E. (1995). On Becoming Skillful: Patterns and constraints. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 66(3), 173-183.

Garber, C.E., Blissmer, B., Deschenes, M.R., Frankklin, B.A., Lamonte, M.J., Lee, I.M., … Swain, D.P. (2011). American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise. American College of Sports Medicine, 43(7), 1344-1359.

Hodges, P.W., & Richardson, C.A. (1999). Altered trunk recruitment in people with low back pain with upper limb movement at different speeds. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 80(9), 1005-1012.

Magill, R. A. (2011). Motor learning and control: Concepts and applications (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

McGill, S.M., Childs, A., & Liebenson, C. (1999). Endurance times for low back stabilization exercises: Clinical targets for testing and training from a normal database. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 80(8), 941-944.

McGill, S. (2007). Low back disorders: Evidence-based prevention and rehabilitation (2nded.). Windsor, ON: Human Kinetics.

McGill, S.M., & Karpowicz, A.K. (2009). Exercises for spine stabilization: Motion/motor patterns, stability progressions, and clinical technique. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 90(1), 118-126.

Mohr, A.R., Long, B.C., & Goad, C.L. (2014). Foam rolling and static stretching on passive hip flexion range of motion. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/jsr.2013-0025

MRM Kinetics (2015). Medical questionnaire. Retrieved fromhttp://www.mrmkinetics.com/downloads

Page, P., Frank, C., & Lardner, R. (2014). The Janda approach to chronic pain syndromes: Preserving the teachings of Dr. Vladimir Janda. Retrieved from http://www.jandaapproach.com/the-janda-approach/jandas-syndromes/

Sullivan, K.M., Silvey, D.B.J., Button, D.C., & Behm, D.G. (2013). Roller-massager application to the hamstrings increases sit-and-reach range of motion within five to ten seconds without performance impairments. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 8(3), 228-229.

Therapeutic Exercise (2015). Medical Dictionary. Retrieved from http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/therapeutic+exercise

-Michael McIsaac