Low back pain is prevalent in more than 60% of the North American population (University of Maryland Medical Center, 2014). 85% of this number is of unknown etiology (McGill, 2007). Thus, low back pain is a common problem that many people have, including my clients. As a kinesiologist working in a post-rehabilitation setting, my job is to improve the performance measures (i.e., mobility, stability, strength and power) of individuals recovering from injuries, after being cleared to proceed from a medical professional.

In the following sections, I would like to provide a step-by-step process of stabilizing a client’s low back. The program will be predicated on an individual with a flexion-intolerant lumbar spine.

When training a client with any type of discomfort, the first recommended step is to discover what has been causing the pain (McGill, 2010). Often flexion is a dynamic movement and static postural pattern that irritates the low back of my clients. This is also a posture quite common in the American population, as most adults spend 2.8 hours in sedentary positions watching television (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2013). Another study by Matthews et al. (2008) discovered that from 6,329 participants in the study between 2003 and 2004, an average of 7.7 hours a day was spent between seated and sedentary activities. Once I understand the provocative movement, I can avoid repeating this during a training session. Moreover, I can help encourage the client to avoid this movement throughout daily tasks (i.e., to be aware of good posture and avoid slouching while performing desk-based work).

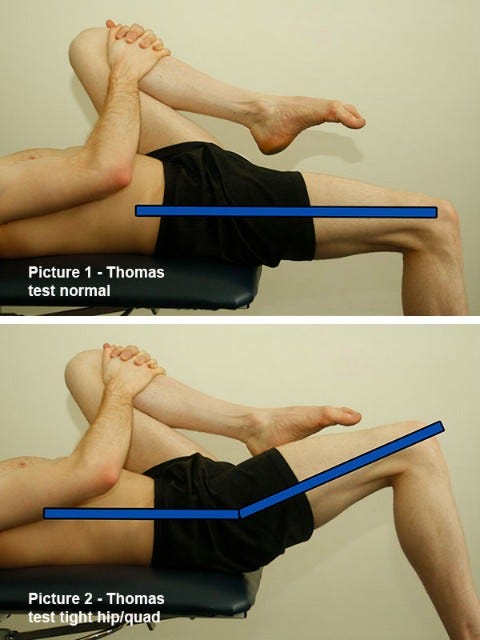

The second step is to ensure range of motion above and below the lumbar spine. That is, I want to make sure there is adequate range in the hips and thoracic spine. The rationale is that if these regions lack range and control, they may cause compensatory movements at the lumbar level. For example, facilitated psoas muscles and erector spinae muscles cause an anterior tilt at the pelvis. This is also known as lower crossed syndrome (Page, Frank & Lardner, 2014). This places the hamstrings in a lengthened position. In turn, performing a lifting movement such as the deadlift pulls the spine into flexion due to a lack of available range in the hamstrings. This movement places flexion upon an already flexion- intolerant low back. Enhancing mobility in the hips can be performed through self-myofascial release and static stretching of the psoas and rectus femoris muscles. Foam rolling the erector spinae can also help relax these muscles as well.

After establishing mobility in the hips and upper back, stability of the low back becomes the third step. Although MacDonald, Moseley and Hodges (2006) have established that building endurance muscles of the lumbar spine is efficacious, how the movements are performed (i.e., avoiding spinal flexion during the exercise) should precede improving a performance measure such as endurance. It should be noted that endurance training can be achieved by both good and bad exercise form. In the case of a painful/recovering low back, there is less room for suboptimal movement quality. Thus, establishing movement control and coordination should occur before building endurance (McGill, 2010).

The fourth step is to develop endurance within the muscles of the lumbar spine. Particular muscles such as the multifidus are stabilizers of the low back and are composed largely of type 1 muscle fibers (MacDonald et al., 2006). This suggests that the multifidus should be targeted by exercises with higher repetitions and/or isometric positions, to elicit changes upon the endurance qualities of the stabilizing muscle. When targeting the multifidus, conscious attention should be placed upon co-contraction of surrounding musculature as well (McGill, 2010). This is because during robust movement patterns such as the deadlift, many muscles are contracting at once. McGill (2010) has also demonstrated that isolating muscles tends to result in less stability. Thus, when performing a movement like a bird-dog to stimulate the multifidus, attention should be paid to contracting the abdominal wall as well in order to foster co-contraction and stiffness around the vertebrae of the low back.

The fifth step is to build strength. A fundamental movement such as the deadlift is a good choice. This is because the deadlift is fundamental (i.e., it is used to lift objects off of the floor) and it develops the hip recruitment and hip extensor strength while sparing movement of the low back (Reiman, Bolgla, & Loudan, 2012).

Low back pain can have many causes. Awareness of the etiology enables us to develop a foundation to build a program that improves performance while reducing pain. By following a pragmatic approach, we can optimize performance outcomes, improve the health of the individual and mitigate pain in the low back.

References

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2013). American time use survey—2012 results U.S. department oflabor. Retrieved February 5, 2014, from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/atus.pdf

American time use survey—2012 results U.S. department oflabor

MacDonald, D. A., Moseley, G. L., & Hodges, P. W. (2006). The lumbar multifidus: Does the evidence support clinical beliefs? Manual Therapy, 11, 254-263.

The lumbar multifidus: Does the evidence support clinical beliefs?

Matthews, C. E., Chen, K. Y., Freedson, P. S., Buchowski, M. S., Beech, B. M., Pate, R. R., & Troiano, R. P. (2008). Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003-2004. American Journal of Epidemiology, 167(7), 875-881.

Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003-2004

McGill, S. (2010). The painful lumbar spine.IDEA Fitness Journal,7 (1), 32-37.

McGill, S. (2007). Low back disorders: Evidence-based prevention and rehabilitation(2nd ed.). Windsor, ON: Human Kinetics.

Page, P., Frank, C., & Lardner, R. (2014). The Janda approach to chronic pain syndromes: Preserving the teachings of Dr. Vladimir Janda. Retrieved February 5, 2014 from http://www.jandaapproach.com/the-janda-approach/jandas-syndromes/

The Janda approach to chronic pain syndromes: Preserving the teachings of Dr. Vladimir Janda

Reiman, M. P., Bolgla, L. A., & Loudan, J. K. (2012). A literature review of studies evaluating gluteusmaximusand gluteusmedius activationduring rehabilitation exercises. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 28(4), 257-268.

A literature review of studies evaluating gluteus maximus and gluteus medius activation during rehabilitation exercises.

University of Maryland Medical Center (2014). Low back pain. Retrieved February 5, 2014, from http://umm.edu/health/medical/altmed/condition/low-back-pain

Low Back Pain

-Michael McIsaac