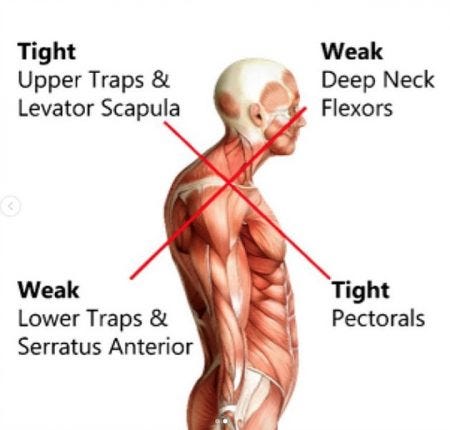

Upper crossed syndrome (UCS) is characterized by muscle imbalances, which create joint, postural, and movement dysfunctions in the cervical and thoracic regions (Page, Lardner, & Frank, 2010). One defining characteristic of UCS is thoracic/thoracolumbar hyperkyphosis; joint positions, which can decrease scapular and glenohumeral stability, deepen muscle imbalances, and provocate joint degeneration (Page et al., 2010).

Thus, it is imperative to identify, and assess the degree of, thoracic hyperkyphosis present in an individual. As a means of appreciating how one might screen for thoracic spine restriction, the following will consider 5 thoracic spine rotation (TSR) screens, their utility, applicability, and efficaciousness in this author’s practice in post-rehabilitation.

Generally, the functional movement screen (FMS) is implemented to capture large and robust movement patterns, as a first step in screening for thoracic spine restrictions, among other aberrant motions (Cook, Burton, Hoogenboom, & Voight, 2014). The FMS is applied first to save time performing smaller, more intricate breakout tests such as the TSR screen; if the client scored a 2/2 on the shoulder mobility screen, this author would likely skip the specific thoracic rotation test; such a score would demonstrate adequate mobility in the thoracic spine and glenohumeral joint (Cook et al., 2014).

If, however, the shoulder mobility screen indicated a 1/1 or asymmetrical score (i.e. 3/2, or 1/3), this author would implement a TSR screen to determine if mobility exceeded 45°; greater than 45° rotation is considered adequate (Titleist Performance Institute, 2013). The following will explore 5 variations of measuring TSR.

Johnson, Kim, Yu, Saliba, and Grindstaff (2012) provided 5 different variations of performing TSR screen with 46 healthy volunteers. Two examiners performed the tests over a 48-hour period with subjects, whereby intertester and intratester reliability was measured. Briefly, the 5 TSR screens included the: seated rotation screen (bar along the inferior border of the shoulders), seated rotation screen (bar on front of the shoulders), half kneeling rotation screen (bar in front of the shoulders, half-kneeling rotation test (bar on back of the shoulders), and lumbar-locked rotation screen (Johnson et al., 2012). Each screen was performed 3 times per side by each examiner, and averages were used for data analysis. TSR screens were performed twice by each examiner on day 1 to measure intertester reliability; day 2 included 1 round of tests for each examiner to determine intratester reliability between days (Johnson et al., 2012).

Results indicated that the same clinician could measure the 5 techniques reliably within a day, and between days (Johnson et al., 2012). It should be noted, however, that intertester reliability was highest with the seated rotation (bar in front) and lumbar-locked positions (Johnson et al., 2012). Such information is pertinent to this author’s practice, as there is a possibility that other kinesiologists on the team may assist in a client’s post-rehabilitation program (i.e., maintaining intertester reliability). Having considered the intratester and intertester reliability of the 5 TSR screens, the following will explore this author’s justifications for implementation of the seated thoracic spine rotation screen (STSR) (bar on back) in his practice.

Below is a link to this author’s YouTube channel demonstrating a modified STSR screen (bar behind shoulders):https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=THCr2h6ROaA&list=PLD5Xk-dZZYNr4H7b0I9e5d60YT5rho4Tk For brevity, STSR screen to the left is demonstrated. However, during a legitimate STSR screen with a client, both sides would be evaluated. This author has modified the STSR screen to include a yoga block between the knees. Such a modification helps indicate if the pelvis is shifting during the screen; if the pelvis shifts, it may create the illusion of adequate thoracic mobility. Pelvic motion is indicated if the end of the yoga block begins to move after initiation of thoracic rotation.

The bar is also placed behind the back instead of the front, and the client is cued to “stick the sternum out”; it is the author’s opinion that it is more difficult for the client to compensate with forward/lateral flexion and scapular movement to achieve rotation in this position, compared to the placement of the bar on the front. The bar is not placed along the inferior border of the scapula, because it is the author’s opinion that his clients often find it difficult to force the elbows far enough back to “hook” the bar with their elbows. Please refer to the PDF article of Johnson et al. (2012) in the reference list below for visuals. Finally, lumbar-locked thoracic mobility screens have been excluded because the author’s clientele are often recovering from neck/shoulder injuries; such positions of the aforementioned test requires clients to place their hands behind their head in the direction they are rotating. The author noted that the arm position often irritates clients’ necks and shoulder regions. Thus, such a TSR screen has been omitted.

In conclusion, this author has been implementing a modified version STSR screen as a means of determining the degree of restriction in the upper back, although evidence has established that reliability is higher for the front bar position (Johnson et al., 2012). Despite reasoning for the modified STSR screen, research has at least encouraged this author to become aware that similar versions of the screen are reliable, if a decision is made to eventually change the style of the TSR screen.

References

Cook, G., Burton, L., Hoogenboom, B.J., & Voight, M. (2014). Functional movement screening: The use of fundamental movements as an assessment of function – Part 2. The International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 9(4), 549-563.

Johnson, K., Kim, K.M., Yu, B.K., Saliba, S., & Grindstaff, T.L. (2012). Reliability of thoracic spine rotation range-of-motion measurements in healthy adults. Journal of Athletic Training, 46(1), 52-60.

Page, P., Lardner, R., & Frank, C. (2010). Assessment and treatment of muscle imbalances: The Janda approach. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Titleist Performance Institute (2013). The seated trunk rotation test. Retrieved from http://www.mytpi.com/articles/screening/the_seated_trunk_rotation_test

-Michael McIsaac