Eating disorders (EDs) can be characterized by extreme under eating and overeating to manage weight, which can manifest into significant problems with both psychosocial (i.e., shame, anxiety) and physical function (i.e., obesity).1 Ultimately, EDs are a resultant behavioral product between the interaction of an individual’s beliefs and feelings.2 As such, nutritionists that manage EDs must change the underlying beliefs and feelings of said manifested behavior. One method of intervention could include motivational interviewing (MI). Thus, as a means of appreciating such an interviewing approach, the following will explore MI and this author’s use of the same with the general population.

In order to modify behaviors, Bundy2(43) indicated that although intrinsic motivation, or the intent to change, is a critical factor, many other factors must be involved in a dynamic interplay to reach such an end. Other factors required to manage and influence behaviour behind EDs include: the beliefs underlying the behavior (mentioned previously), the value of it, the perceived costs and benefits of changing, the barriers to changing, beliefs behind the ability to perform the behavior change, and social support from others.2(43) As such, oversimplified interventions (though well-intended) such as educating clients of the dangers of EDs is not enough to elicit effective and long-term changes. MI can help bridge the gap.

Bundy2(43) stated that many individuals with chronic illnesses experience psychologically challenging and physically debilitating treatments to help resolve underlying issues. Moreover, such illnesses require a high degree of self-management, which by association, demands a high level of motivation. Motivation can be defined as a state of readiness or eagerness to change, and MI is a cognitive-behavioral technique that aims to help patients identify and change behaviors in question.2(43) Ultimately, such an approach can help individuals modify or change behaviors that could be placing them at risk of developing a health problem or hindering optimal management of a chronic illness.2(43)

MI, according to Bundy,2(43)is considered a relatively supportive, transparent, and simple talk therapy predicated on the principles and goals of cognitive-behavioral therapy which includes:

- understanding an individual’s thought process behind a problem

- identifying and measuring emotional reactions to the problem

- identifying how thoughts and feelings produce patterns in behavior

- challenging the individual’s thought patterns to implement an alternate behavior

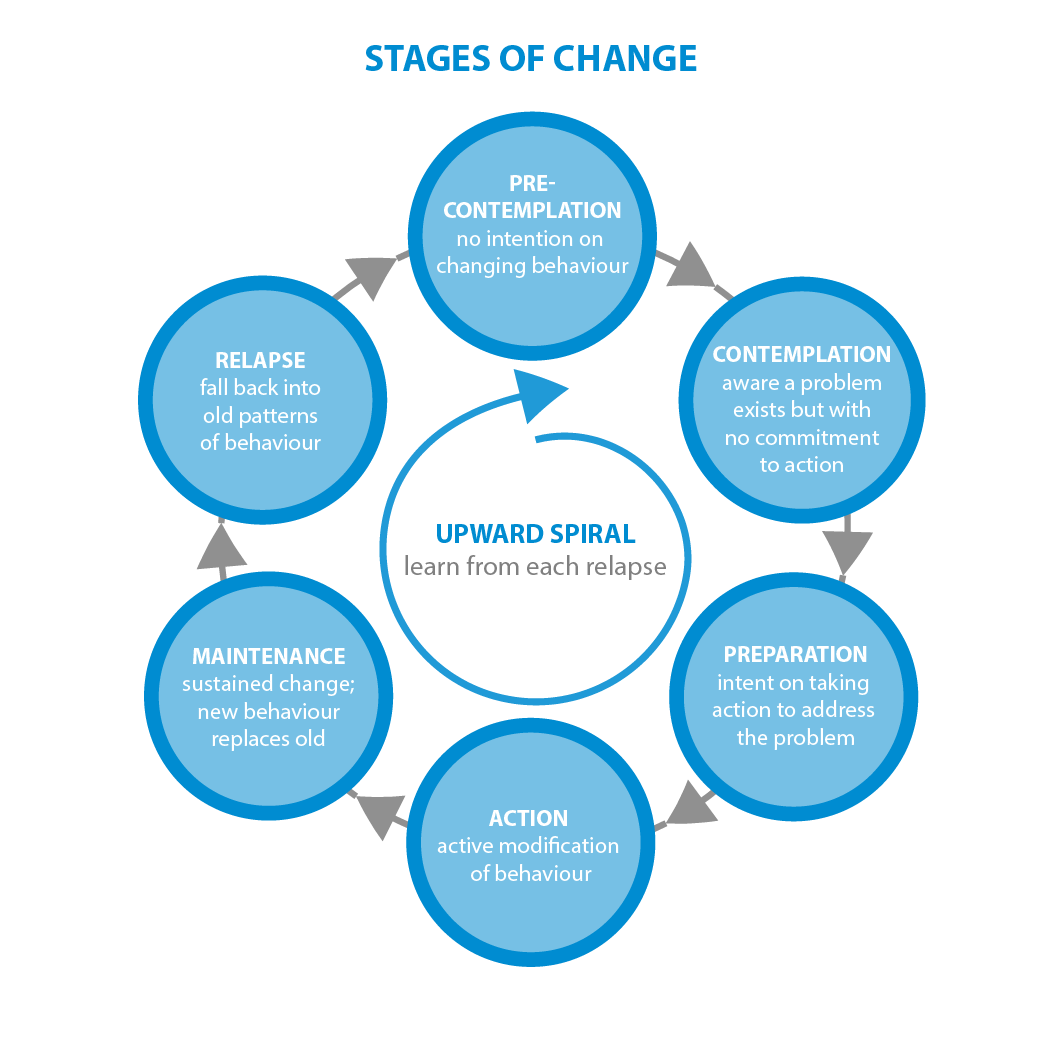

In addition to the aforementioned four goals of MI, it is also relevant to acknowledge how individuals tend to change behaviour; Bundy2(44) suggested individuals change or modify behaviour in smaller stages to include a pre-contemplation stage (not considering change), contemplation stage (considering change but have no plan), planning (developing defined strategies and actions for change), and maintenance (ongoing efforts to maintain changes). Understanding what stage of change an individual is in helps the professional determine how to implement MI.

MI achieves the previously mentioned four cognitive-behavioral goals by implementing 8 strategies according to Bundy2(44):

- giving advice regarding behaviors to change

- removing barriers such as access to help

- providing choice and ensuring the individual is free to seek further help or quit devoid of judgement

- decrease desirability or the mixed feelings towards changing behavior

- ensuring the nutritionist practices empathy

- receiving feedback from social support networks

- clarifying goals and ensuring feedback is compared to a standard

- ensuring the professional is providing active help (providing referrals to other professionals)

Such steps will help guide individuals through the stages of change while also helping the nutritionist meet the underlying goals of MI (understanding an individual’s thought process behind a problem, identifying and measuring emotional reactions to the problem, identifying how thoughts and feelings produce patterns in behavior, challenging the individual’s thought patterns to implement an alternate behavior).2(43)

This author has used some of the aforementioned constituents of MI, but have not exhausted all measures. In addition to the underlying 4 goals of MI and the 8 strategies to achieve the same, this author has not fully implemented conditions that facilitate change: expressing empathy, avoiding argument, supporting self-efficacy, rolling with resistance, and developing discrepancy.2(44)Of the 5 conditions outlined, this author has identified deficits in supporting self-efficacy and expressing empathy.

When clients have reported failing to maintain a lifestyle change, this author could have attempted to help them reframe their thoughts from a point of failure to one of self-acceptance. Furthermore, helping clients develop their own strategies to overcome challenges would be more effective, as opposed to dictating goals. This author also tended to provide strategies to reach goals in the absence of deeper listening and understanding (expressing empathy). Considering that empathy is fundamental to talk therapies, this author will endeavor to listen more, and talk less.2(44)

In conclusion, EDs can be characterized by extreme under eating and overeating to manage weight, which can manifest into significant problems with both psychosocial (i.e., shame, anxiety) and physical function (i.e., obesity). Individuals who require behavior modification but lack intrinsic motivation and exude ambivalence to change might be candidates for MI. Such an intervention, as part of a larger and more inclusive strategy, could help clients reach goals in a definitive, meaningful, and sustainable fashion.

References

1. MacDonald P, Hibbs R, Corfield F, et al. The use of motivational interviewing in eating disorders: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200:1-11. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.05.013.

2. Bundy C. Changing behaviour: Using motivational interviewing techniques. J R Soc Med. 2004;97(44):43-47.

-Michael McIsaac