Modern Western diets have experienced a drastic change compared to civilizations of 10,000 years ago (Ilich, Kelly, Kim, & Spicer, 2014). Today, approximately 70% of total energy emanates from refined vegetable oils, processed foods, sugars, and alcohol (Ilich et al., 2014). Such an aberration in nutrition quality over a relatively short period in human history has likely contributed to many chronic diseases of present day. Thus, developing effective methods to assist individuals in modifying behaviours and eating habits is critical in reducing the incidence of disease and restoration of health. In the following sections, this author will explore the utility and limitations of smartphones and nutritional software as a means of reaching such an end.

Currently, approximately 60% of Americans use cell phones, and half of said population access applications (apps) on a daily basis (Ipjian & Johnston, 2017). Additionally, 40,000-60,000 health and wellness apps exist for smartphones, providing a plethora of options for the end user (Ipjian & Johnston, 2017). Ultimately, such an abundance of apps and quick access via smartphone provides convenience, increasing the likelihood of use and adherence. Ipjian and Johnston (2017) stated that when used as a client-counseling tool, apps can facilitate health care professionals in educating clients on specific dietary modifications, and to promote client accountability. Additionally, said apps have the potential to assist in the evolution of the health care system; such software can help improve health outcomes, reduce health disparities, and control medical costs (Ipjian & Johnston, 2017). Having considered the abundance of apps and easy access, the following sections will explore the efficaciousness of such software.

Ipjian and Johnston (2017) chose to use the MyFitnessPal application as a means of electronically tracking nutrient intakes, with exclusive focus on sodium consumption; a nutrient generally accepted to be consumed by North Americans in excess of the target of <2300mg/day. 114 participants (18-80 years of age) were accrued for the 28-day study, and 33 subjects were chosen for the trial and randomly assigned to a MyFitnessPal group or a journal group (writing down food consumption) (Ipjian & Johnston, 2017). During the initial intake, subjects completed a health history questionnaire, Rapid Eating and Activity Assessment for Patients, in addition to a validated questionnaire, which assessed diet quality (Ipjian & Johnston, 2017). The researchers collected blood pressure, body weight, body fat, height, and waist circumference. Finally, sodium levels were measured via urine analysis at baseline and during the experiment.

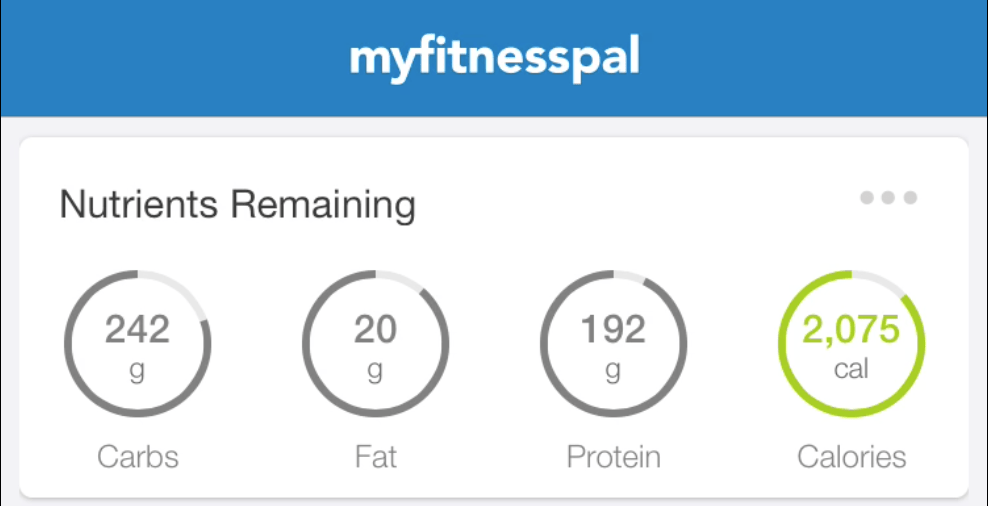

Subjects using the MyFitnessPal app to monitor daily sodium consumption over the course of 28 days achieved a mean reduction in urinary sodium excretion of approximately 19% (Ipjian & Johnston, 2017). Interestingly, Ipjian and Johnston (2017) showed that the journal group’s urinary sodium excretion measures increased 11% compared to baseline measures. Such results help support the utility in using such applications for self-monitoring, while highlighting some of the limitations of journaling. Although applications like MyFitnessPal have particular advantages (i.e., ease of use, quick access, calculation of micronutrients/macronutrients/macronutrient ratios, and total calories consumed compared to target calories), it is also relevant to provide a balanced view of such technology.

Apps such as MyFitnessPal require a degree of literacy and adherence from the user; one must become accustomed to finding and inputting food. Sometimes, the serving size within the app requires the user to measure and weigh foods, allowing potential for individuals to approximate portion sizes rather than measuring. Other limitations include a lack of information on foods; sometimes there is no database for foods that one may consume (i.e., eating a pizza at a privately-owned restaurant; the database is unlikely to include the information on said restaurant). Compared to computerized dietary analysis software, MyFitnessPal can fall short; some computerized software outlined by Lee and Nieman (2013) can have a database of foods of over 39,000 items. Moreover, online apps often provide simpler graphs and tables that nutritionists may find limiting in detailed information (Lee & Nieman, 2013).

In conclusion, although apps like MyFitnessPal have some drawbacks as previously outlined, such software still has merit. Not only can MyFitnessPal help guide one’s eating behaviours; such technology can also educate and assist the client in choosing food type and proportions via association with macronutrient and micronutrient information. Eventually, individuals would be able to wean themselves from the application, using it like a “training wheel” until they are able to competently choose and consume the appropriate foods for their health goals.

References

Ilich, J. Z., Kelly, O. J., Kim, Y., & Spicer, M. T. (2014). Low-grade chronic inflammation perpetuated by modern diet as a promoter of obesity and osteoporosis. Archives of Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology, 65(2), 139-148.

Ipjian, M. L., & Johnston, C. L. (2017). Smartphone technology facilitates dietary change in healthy adults. Nutrition, 33, 343-347.

Lee, R. D., & Nieman, D. C. (2013). Nutritional assessment (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

-Michael McIsaac