Obesity is not only a disease, but an epidemic driven by hormones, behavior, genetics, as well as bacteria, physiology, pathogenic pathways, and culture.1 Obesity has continued to extend its grip reaching Asia, the Near and Middle East, Western Pacific regions, and Sub-Saharan Africa.2

Modern day living is considerably different from Homo sapiens 10,000 years ago, and within the last 200 years, the risk of obesity and diabetes began to rise in a slow and insidious fashion.2(28)As a means of appreciating culture and its influence upon obesity, the following will consider the same.

Strikingly, 2008 marked a point in human history where the number of obese people exceeded the number of individuals suffering from starvation and malnutrition; over 1.9 billion people are now overweight, 600 million of said population categorized as obese, with 1 in 10 children afflicted with obesity worldwide.2(28)

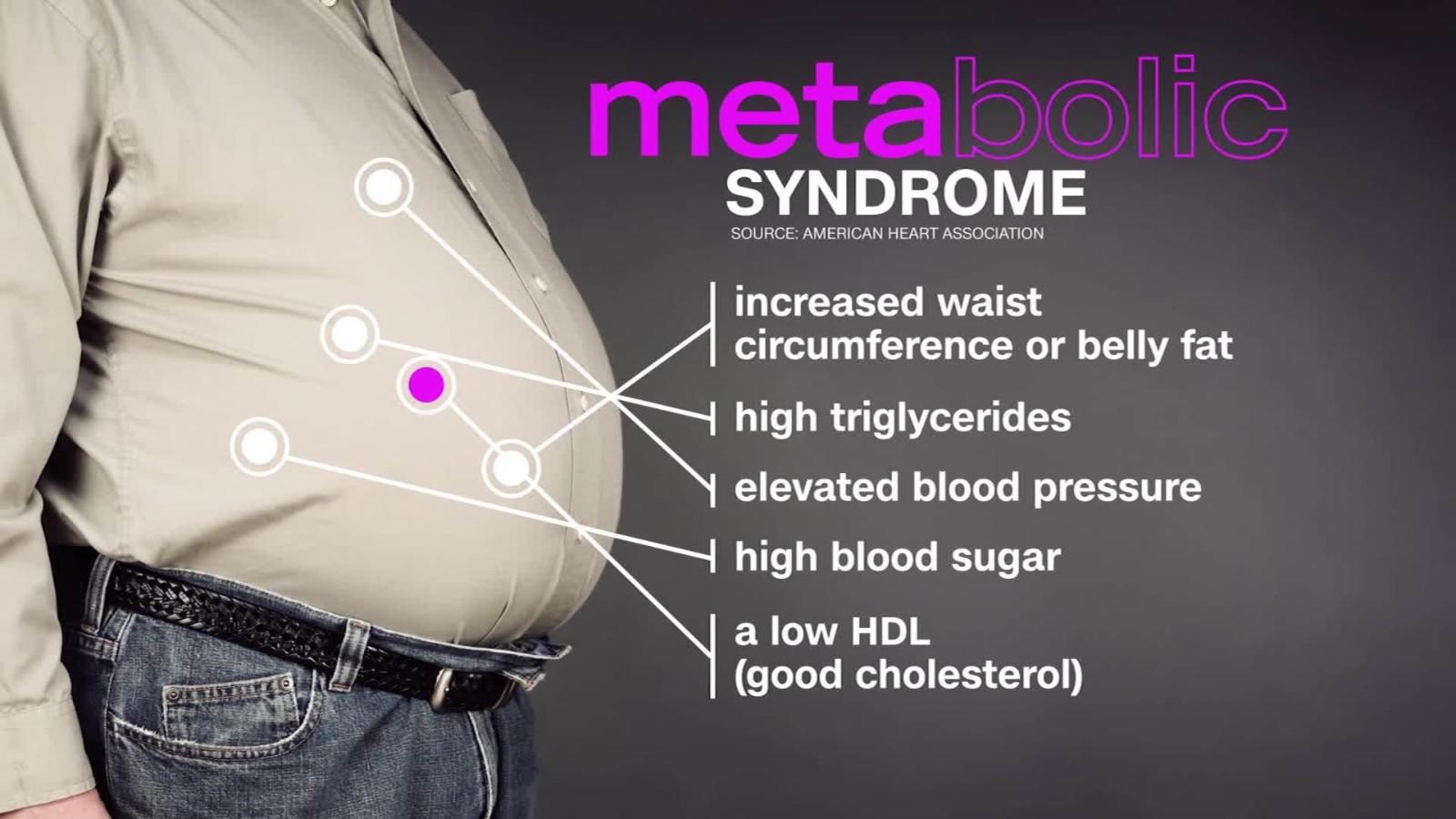

Furthermore, obesity is strongly associated with several chronic illnesses including heart disease, stroke, hypertension, pancreatitis, osteoarthritis, cancer, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes.2(28) Among the most prevalent diseases associated with obesity is type 2 diabetes (T2D); a condition so closely related to obesity that a new term, known as diabesity, has been coined to describe said relationship.2(28)

Evolutionary anthropology, according to Kirsch,2(28)attempts to analyze the evolutionary basis of obesity and T2D and why they manifested. Historically, obesity existed since the Upper Paleolithic era (between 50,000 and 10,000 years ago) although sparse in reach and number during prehistory.2(36)

Largely, obesity and T2D as seen in modern Europe, was a near exclusive problem amongst some affluent sections of society.2(37)During the late 18thcentury, however, obesity became a common condition within the English upper classes; a point in history also marked by technological innovations that laid the groundwork for social, economic, and cultural changes that would occur during the Industrial revolution.2(37)

Rapid urbanization and aggressive changes in agriculture (i.e., farming machines and fertilizers) expedited the production of food in a way not seen before. Such advances gave birth to unprecedented levels of food production and excess, fundamentally changing living conditions and quality of life.2(37) During the latter part of the 19thcentury, Kirsch2(37) stated that the majority of people blanketed in the industrialized world (Europe and North America) had access to sufficient amounts of food.

Yet, such a historical point also marked the slow emergence of obesity and T2D.2(37) Though not ubiquitous in nature, obesity and T2D rates began to rise, temporarily blunted by the great depression and two world wars. However, after said period, industrialized countries began to experience abundance of nutrient-rich foods.2(38)

Such a change in living conditions and food abundance produced a double-edged sword; although famine and starvation began to lower, excessive food production and access to the same began to produce metabolic disease.2(38) Since then, obesity and T2D have grown in an aggressive fashion during the last 30 years and is now considered conditions of affluence.2(38)

Modern day living, to include an overabundance of food and less physical activity (increased use of mechanized transportation and increased sedentary behavior), is strongly contrasted to the Upper Paleolithic era described in earlier sections. Such additional insights into our ancestors’ past helps shed light on changes observed in modern day Westernized societies.

Another marked change in human history occurred during the Neolithic epoch; such a point (circa 10,000 years ago) was characterized by a change in food gathering strategies. The Upper Paleolithic era demanded that individuals hunt for food as well as forage for fruit.2(40-41)Such requirements for sustenance led individuals to eat meats that were generally lean and fruits that were available during the season.

Furthermore, the degree of physical activity required to carry out said tasks were dramatically higher than that of modern-day people.2(41) However, the Neolithic period marked a historical point where agricultural methods (domestication of animals and large-scale production of crops) negated the need to spend time and energy hunting ang gathering food.2(41)

The Neolithic period not only marked a reduction in foraging strategy; it also changed the types of foods consumed and quantity, marked largely by high carbohydrate crops to include rice, potato, and barley.2(42) Together with the Industrial revolution, both eras marked strong changes in food consumption and physical activity, now known as the first epidemiologic transition and second epidemiologic transition, respectively.2(42)

Said epidemiologic transitions likely gave birth to the third epidemiologic transition that occurred during the 21stcentury; modern advances in technology from the industrial revolution and agriculture from the Neolithic era allowed for the successful decline of infectious diseases (better medicine). However, the marked decline of physical activity and excessive access to energy dense food increased rates of non-communicable and degenerative disease such as obesity and T2D.2(42)

In conclusion, there is at minimum, a mismatch between modern day environments and those of the Upper Paleolithic era. Striking changes have been noted in both physical activity and food consumption (to include food type-carbohydrates) that occurred in a relatively short period of time in recorded human history. Ultimately, such unabated declines in human movement and increases in energy-dense food consumption is likely to perpetuate obesity and T2D if interventions regarding the same remain underappreciated.

Reference

1. Mertz L. Taking on the obesity epidemic: Researchers wage a big fat fight in efforts to combat this global health issue. IEEE. 2017;8(4):15-19. doi:10.1109/MPUL.2017.2701491.

2. Kirch S. Diabetes and obesity-An evolutionary perspective. AIMS. 2017;4(1):28-51. doi:10.3934/medsci.2017.1.28.

-Michael McIsaac