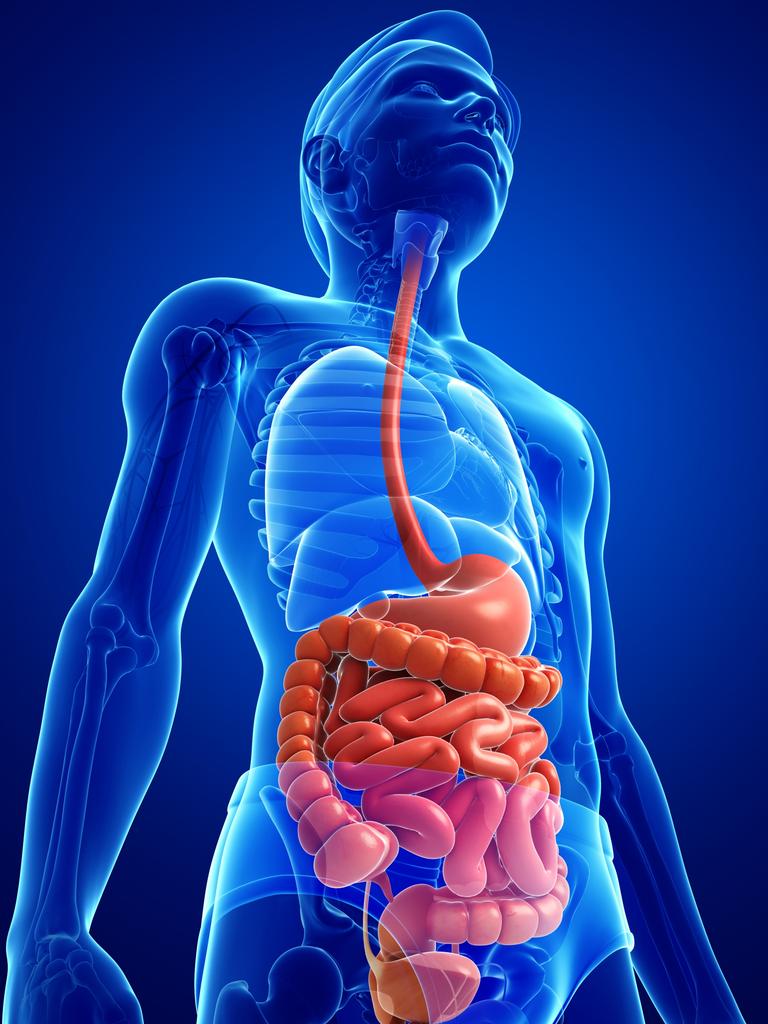

The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is an estimated 16-foot long system, which includes the upper digestive tract (esophagus, oral cavity, stomach) in addition to the lower digestive tract (small and large intestine) and accessory organs (liver, gallbladder, pancreas) (Gropper, Smith, & Carr, 2018). Such a system serves as a semipermeable gateway connecting the outside environment to the delicate internal processes of the human body (Salvo-Romero, Alonso-Cotoner, Pardo-Camacho, Casado-Bedmar, & Vicario, 2015). Therefore, optimal health is largely influenced by the appropriate digestion and absorption of nutrients along the GIT. Said processes are supported by (in addition to other physiological and biochemical events) pancreatic/liver secretions and amino acids to optimize gut function. As a means of appreciating digestion/absorption, the following will consider said accessary organ secretions, key amino acids, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and their relationship to GIT function and health.

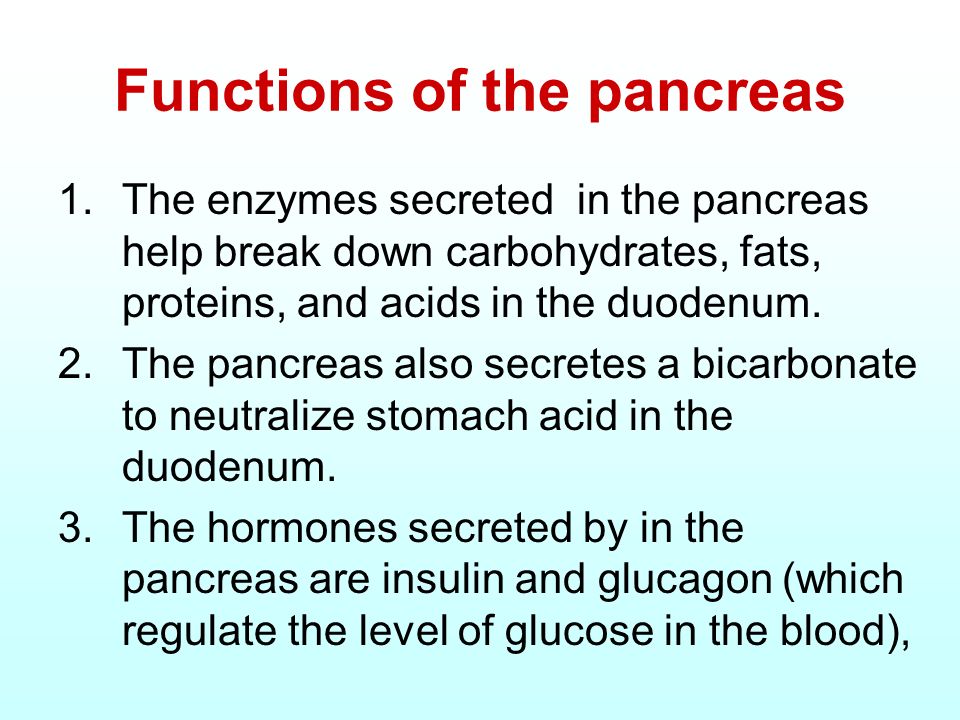

The pancreas is an organ sitting inferiorly to the liver consisting of exocrine and endocrine glands. In relation to digestive function, the exocrine glands are responsible for producing and discharging alkaline pancreatic juice rich in digestive enzymes (Pagana & Pagana, 2014).Such enzymes include chymotrypsin/trypsin (digests proteins), amylase (digests carbohydrates), and lipase (digests fats) which plays an integral role in the breakdown of larger food particles into its constituents (Pagana & Pagana, 2014). The liver is an organ which also produces juices to include cholic acid/chenodeoxycholic acid, known as primary bile acids, that contribute to digestion. Said acids are conjugated to the amino acids glycine and taurine, respectively, and stored in the gall bladder until required (Rees, Crick, Jenkins, Wang, Griffiths, Brown, & Al-Saririeh, 2017). As an aggregate, hepatic and pancreatic secretions work symbiotically to facilitate digestion and absorption of nutrients from food.

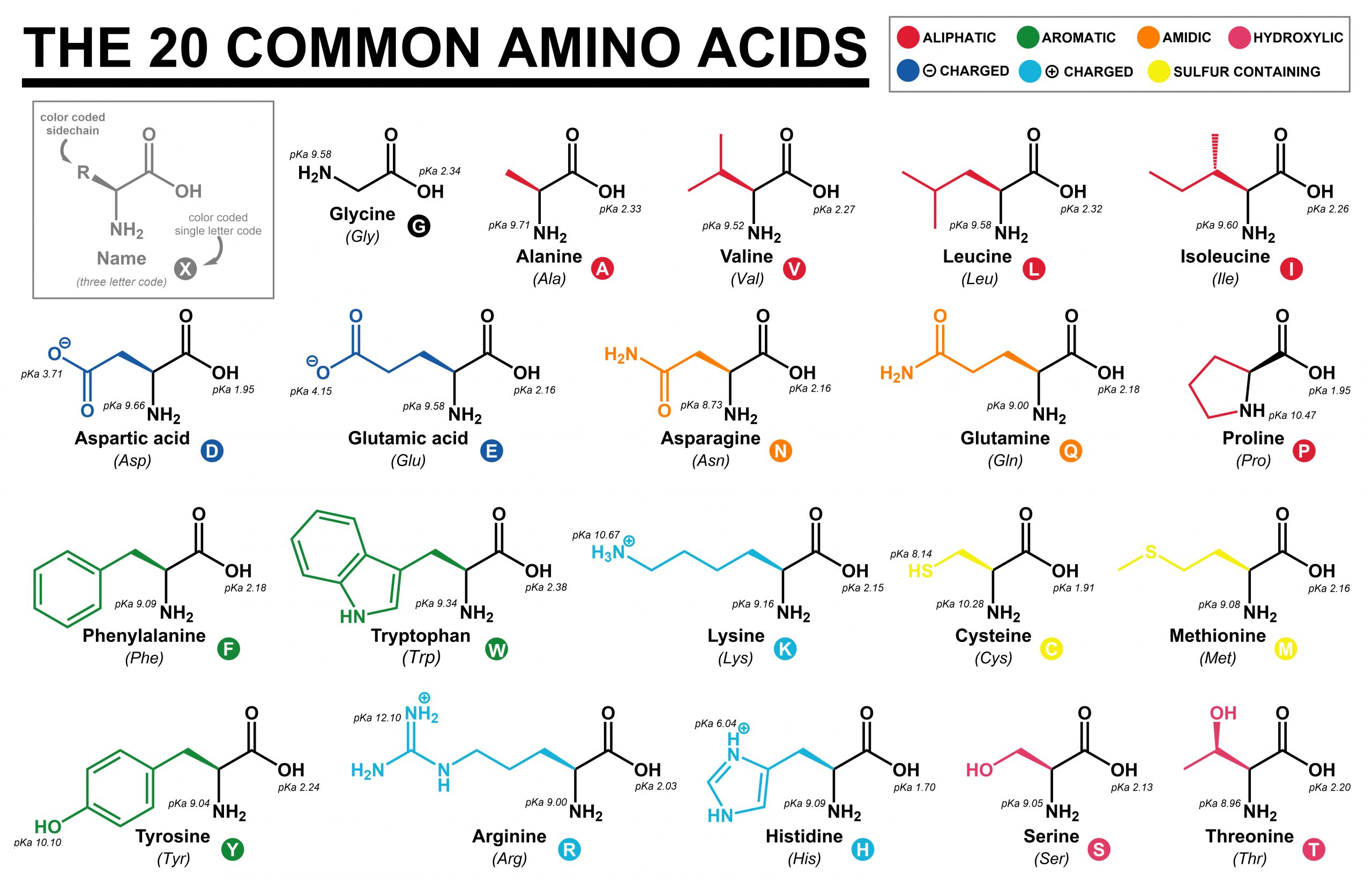

As briefly mentioned in the last section, amino acids are a group of molecules responsible for participating in the production of digestive enzymes. However, amino acids also serve to facilitate digestion and absorption by interacting with the GIT lining. Nie, He, Zhang, Zhang, and Ma (2018) explained that proper functioning of the GIT is not only important for digestion and absorption of nutrients; it also contributes to maintaining overall immune function and health. Aberrations in gut homeostasis is also related to irritable bowel syndrome, type 2 diabetes, obesity, atherosclerosis, and colon cancer. As such, it is paramount that GIT works in an optimal fashion, and amino acids facilitate such a process. Nie et al. (2018) stated that the amino acids arginine, glutamine, and threonine could improve integrity of tight junctions, cell migration, anti-oxidative responses, and mucosal barrier functions in the intestine. Furthermore, amino acids serve as regulators to stimulate intestinal development, immune related function, and nutrient transporters (Nie et al., 2018). The following section will explore amino acids and gut function in greater detail.

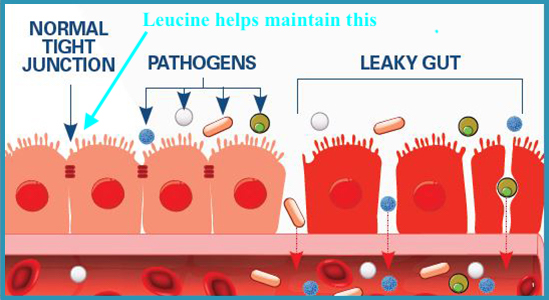

Leucine (Leu) supplementation maintains intestinal homeostasis by enhancing tight junctions along the intestinal wall (Nie et al., 2018). Tight junctions are regions along the intestinal epithelium (along with intestinal mucosa) which helps form a biological barrier between the body (i.e., bloodstream and other organs) and outside luminal pathogens and antigens (Feng, Huang, Wang, Song, & Wang, 2019). Branched chain amino acids (leucine, valine, isoleucine), also known as BCAAs, have been implicated in immunity regulation as immune cells incorporate said amino acids into proteins. Furthermore, BCAAs can serve as substrates for the production of glutamine; another amino acid responsible for supporting immune cell function (Nie et al., 2018). In essence, optimal digestion/absorption/immune function are necessary fundamental pre-requisites to maintenance of health and homeostasis. Despite the presence of optimal amino acids in the diet to support gut function, other factors can induce aberrations in GIT physiology. One such agent is excessive serotonin; a neurotransmitter in which 90% is produced in the GIT, when functioning normally (Stoler-Conrad, 2015).

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter responsible for the regulation of mood, sleep, appetite, sexuality, emesis (vomiting), and gut motility (Lord & Bralley, 2012). The synthesis of serotonin begins with another amino acid tryptophan which is converted into 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) and eventually serotonin. Individuals suffering from neuropsychiatric disorders, such as depression, often have low plasma readings of said substance. However, supplementation of tryptophan helps increase plasma levels and symptoms of depression (Lord & Bralley, 2012). Another effective intervention is the application of serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) whereby serotonin degradation/reuptake is slowed or inhibited (Lord & Bralley, 2012). Such an event allows serotonin to continue exerting its effects for protracted periods of time, to include alleviating depression. However, excessive/mis-managed SSRI use can have negative affects upon the GIT by altering the function of the microbiome in addition to hepatic/pancreatic dysregulation (Milkiewicz, Chilton, Hubscher, & Elias, 2003; Ramsteijn, Jasarevic, Houwing, Bale, & Olivier, 2018). Thus, monitoring gut and accessory organ function is essential when using SSRIs.

In conclusion, the GIT is semipermeable gateway connecting the outside environment to the delicate internal biochemical and physiological processes of the human body. Optimal health is largely influenced by the appropriate digestion and absorption of nutrients along the GIT, in addition to a well-functioning gut lining and immune system. Key amino acids that facilitate such a process include leucine, valine, isoleucine, arginine, glycine, taurine, threonine. However, a diet low in said amino acids or use of drugs such as SSRIs can, sometimes, negatively affect digestion/absorption of nutrients and overall homeostasis.

References

Feng, Y., Huang, Y., Wang, Y., Song, H., & Wang, F. (2019). Antibiotics induced intestinal tight junction barrier dysfunction is associated with microbiota dysbiosis, activated NLRP3 inflammasome and autophagy. PLOS One, 14(6), 1-19.

Gropper, S. S., Smith, J. L., & Carr, T. P. (2018). Advanced nutrition and human metabolism (7thed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Lord, R. S., & Bralley, J. A. (2012). Laboratory evaluations for integrative and functional medicine (2nded.). Duluth, GA: Genova Diagnostics.

Milkiewicz, P., Chilton, A. P., Hubscher, S. G., & Elias, E. (2003). Antidepressant induced cholestasis: Hepatocellular redistribution of multidrug resistant protein (MPR2). Gut, 52(2), 300-303.

Nie., C., He., T., Zhang, W., Xhang, G., & Ma, X. (2018). Branched chain amino acids: Beyond Nutrition Metabolism. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(4), 1-16.

Pagana, K. D., & Pagana, T. J. (2014). Manual of diagnostic and laboratory tests (5thed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

Ramsteijn, A. S., Jasarevic, E., Houwing, D. J., Bale, T. L., & Olivier, J. D. A. (2018). Antidepressant treatment modulates the gut microbiome and metabolome during pregnancy and lactation in rats with a depressive-like phenotype. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/501742

Rees, D. O., Crick, P. J., Jenkins, G. J., Wang, Y., Griffiths, W. J., Brown, T. H., & Al-Saririeh, B. (2017). Comparison of the composition of bile acids in bile of patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreas and benign disease. TheJournal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 174, 290-295.

Salvo-Romero, E., Alonso-Cotoner, C., Pardo-Camacho, C., Casado-Bedmar, M., & Vicario, M. (2015). The intestinal barrier function and its involvement in digestive disease. Revista Espanola De Enfermedades Digestivas, 107(11), 686-696.

Stoler-Conrad, J. (2015, April 9). Microbes help produce serotonin in gut. Retrieved from https://www.caltech.edu/about/news/microbes-help-produce-serotonin-gut-46495

-Michael McIsaac