In my last post, I covered the utility of low carbohydrate/high fat diets. However, one must be cautious to assume such diet is beneficial for all individuals as bio-individuality and circumstance might demand a different intervention. Some individuals exhibit an intolerance to fats in the diet, manifested as loose stools, gut discomfort, and low energy levels; a condition known as steatorrhea (Cho-Dorado, 2017). Left untreated, such an aberration in intestinal digestion/absorption can lead to more serious disruptions in homeostasis and health. As a means of appreciating steatorrhea, the following will explore diagnostic tests and some of the underlying causes of said disease.

As previously mentioned, steatorrhea is a condition that is suspected when stools are large, greasy (high fat content), and foul-smelling (Pagna & Pagna, 2014). Steatorrhea occurs when fat content is high within the stool and can emanate from malabsorption (sprue, Crohn’s disease, Whipple disease) and maldigestion (bile duct obstruction, pancreatic duct obstruction, secondary to a tumor of gallstones) (Pagna & Pagna, 2014). Furthermore, fat analysis from stool samples can assist in differentiating malabsorption or maldigestion; if fats are neutral (in the form of monoglycerides, diglycerides, triglycerides) pancreatic enzymes/bile never interacted with said molecules indicating maldigestion. If the fats are broken down into fatty acids, such a finding would indicate pancreatic/bile interaction and breakdown in the absence of absorption (malabsorption) (Pagna & Pagna, 2014). The following will briefly explore test results and associations to some of the diseases responsible for steatorrhea.

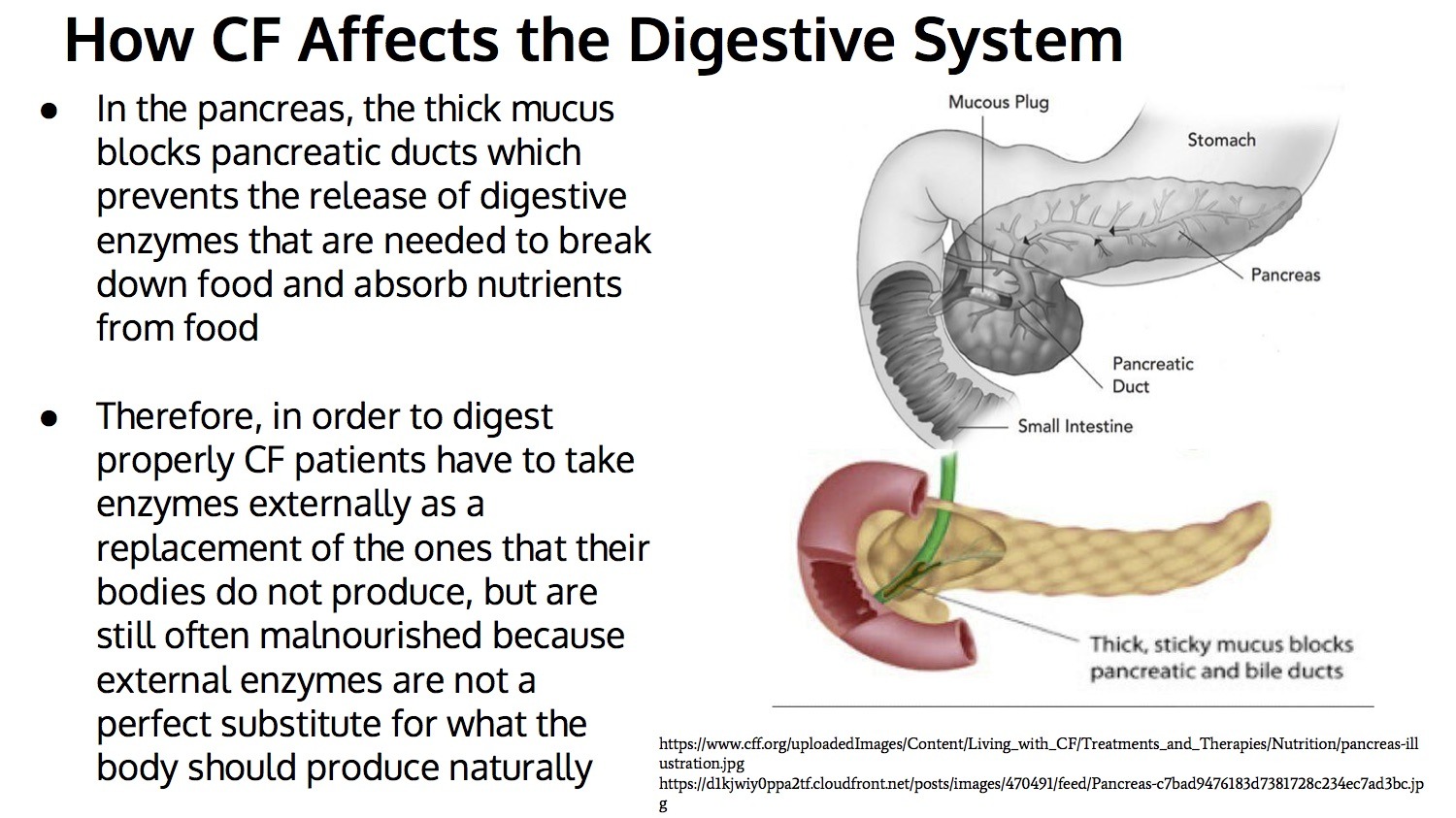

If fecal test results indicate high levels of fats, one possible source could be cystic fibrosis (CF). CF is characterized by an insufficient production of pancreatic enzymes (i.e., pancreatic lipase) responsible for fat breakdown (Bakker, Bodewes, & Verkade, 2011). Consequently, the intestine is unable to absorb fats into the bloodstream, and steatorrhea/suboptimal nutritional status occurs Thus, a cornerstone of CF therapy is to replace pancreatic enzymes to improve both digestion and absorption of fats (Bakker et al., 2011).

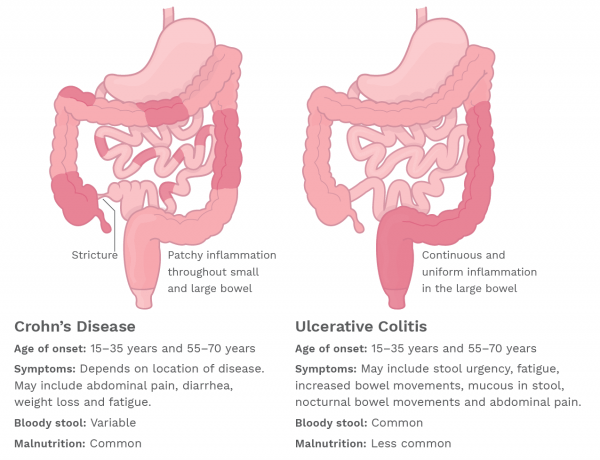

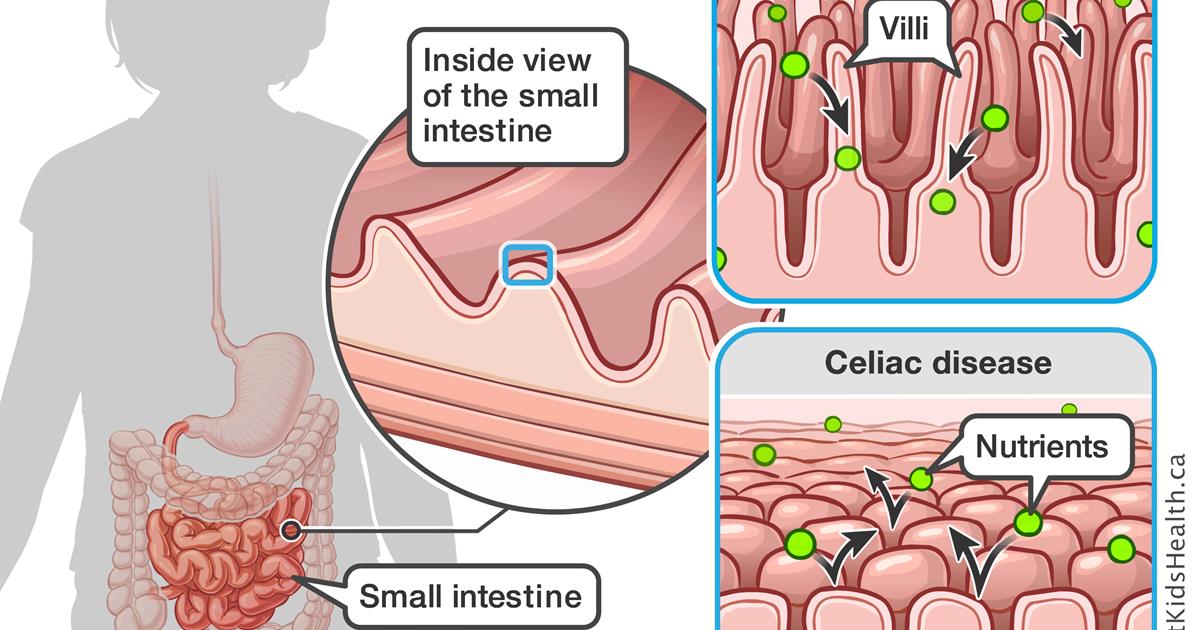

Malabsorption of fats can be secondary to other conditions such regional enteritis (RE) and sprue (Pagna & Pagna, 2014). RE, or Crohn’s disease, is an autoimmune disease, which inflames regions of the intestinal tract, most often around the ileum (about 3.5 meters long). Such inflammation inhibits the absorption of fat (and other nutrients) leading to loose stools and nutrient deficiencies (Jakobiec, Rashid, Lane, & Kazim, 2014). Sprue, or celiac disease (CD) caused by reactivity to gluten, is another inflammatory condition that inhibits fat absorption.

CD is characterized by the innate immune system response, which initiates shortly after ingestion of gluten. The immune response is characterized by activation of the lymphocytes within the surface epithelium, in addition to alterations in the epithelial cells producing cytokines (cell-signalling proteins involved in the immune response), particularly interleukin (IL)-15, which continues the immune response to continued gluten exposure (See, 2006). Ultimately, such a response destroys the intestinal villi (structures, which absorb nutrients) changing the permeability of the intestinal lining (See, 2006). One manifestation of CD is fat malabsorption (Pagna & Pagna, 2014).

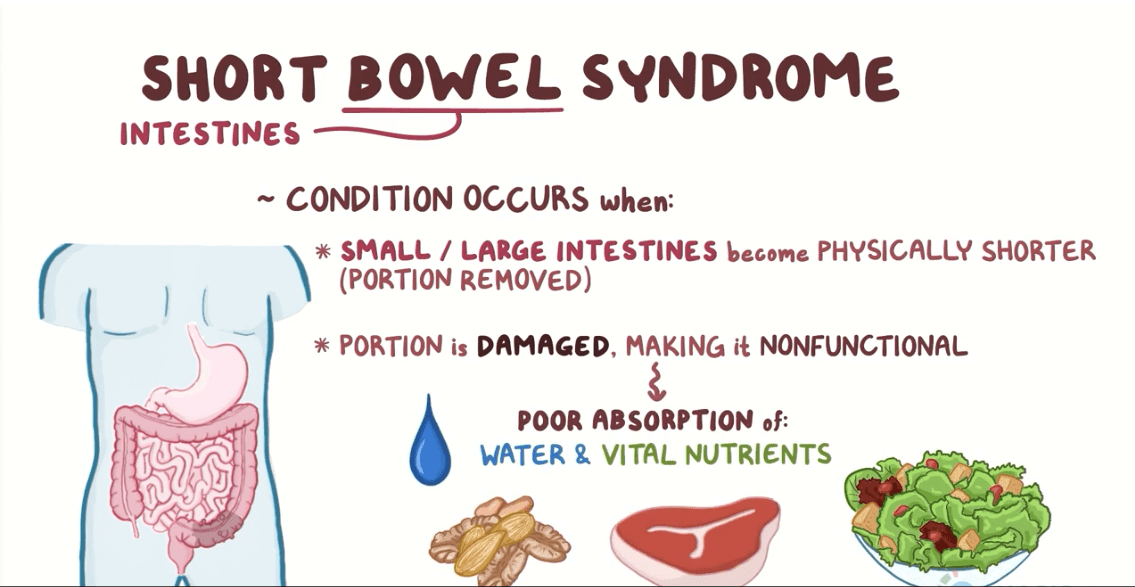

Short gut syndrome (SGS) is another condition that causes steatorrhea. Sukhotnik, Mor-Vaknin, Drongowski, Conran, and Harmon (2004) described SGS asa condition characterized by a loss of intestinal length (surgery), resulting in a reduced ability to digest and absorb food. Specifically, although the capacity to absorb nutrients is decreased following resection, lipid absorption is considered the most vulnerable (Sukhotnik et al., 2004). As an aggregate, the loss of absorptive surface area, compromised intestinal circulation, loweredbile acid pool, and reduced lipase secretion (pancreas) results in poor fat digestion/absorption and steatorrhea (Sukhotnik et al., 2004).

In conclusion, high fat levels in stool can be an indication of deeper pathological conditions. When symptoms are present (greasy stool, low energy, diarrhea, bloating, stomach cramps), deeper tests can help diagnose if the condition is maldigestion or malabsorption. Furthermore, continued screening can help connect maldigestion/malabsorption disorders with a disease state. Such steps can help develop a platform for treatment interventions, ultimately restoring gut health and nutrient utilization. Most importantly, such knowledge should encourage vigelance and remind nutritionists and medical professionals that particular interventions (i.e., low carbohydrate/high fat diets), however useful, may not be appropriate for all individuals all of the time.

References

Bakker, M. W., Bodewes, F. A. J. A., & Verkade, H. J. (2011). Persistent fat malabsorption in cystic fibrosis; Lessons from patients and mice. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis, 10(3), 150-158.

Cho-Dorado, M. (2017, December 19). What is steatorrhea or fatty stool? Retrieved from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/320361.php

Farrell, R. J., & Kelly, C. (2002). Celiac sprue. The New England Journal of Medicine, 346(3), 180-188.

Jakobiec, F. A., Rashid, A., Lane, K. A., & Kazim, M. (2014). Granulomatous dacryoadenitis in regional enteritis (Crohn disease). American Journal of Ophthalmology, 158(4), 838-844.

Pagana, K. D., & Pagana, T. J. (2014). Manual of diagnostic and laboratory tests (5thed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

See, J. (2006). Gluten free diet: The medical and nutrition management of celiac disease. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 21(1), 1-15.

Sukhotnik, I., Mor-Vaknin, N., Drongowski, R. A., Conran, A. G., & Harmon, C. M. (2004). Effect of dietary fat on fat absorption and concomitant plasma and tissue fat composition in a rat model of short bowel syndrome. Pediatric Surgery International, 20(3), 185-191.

-Michael McIsaac