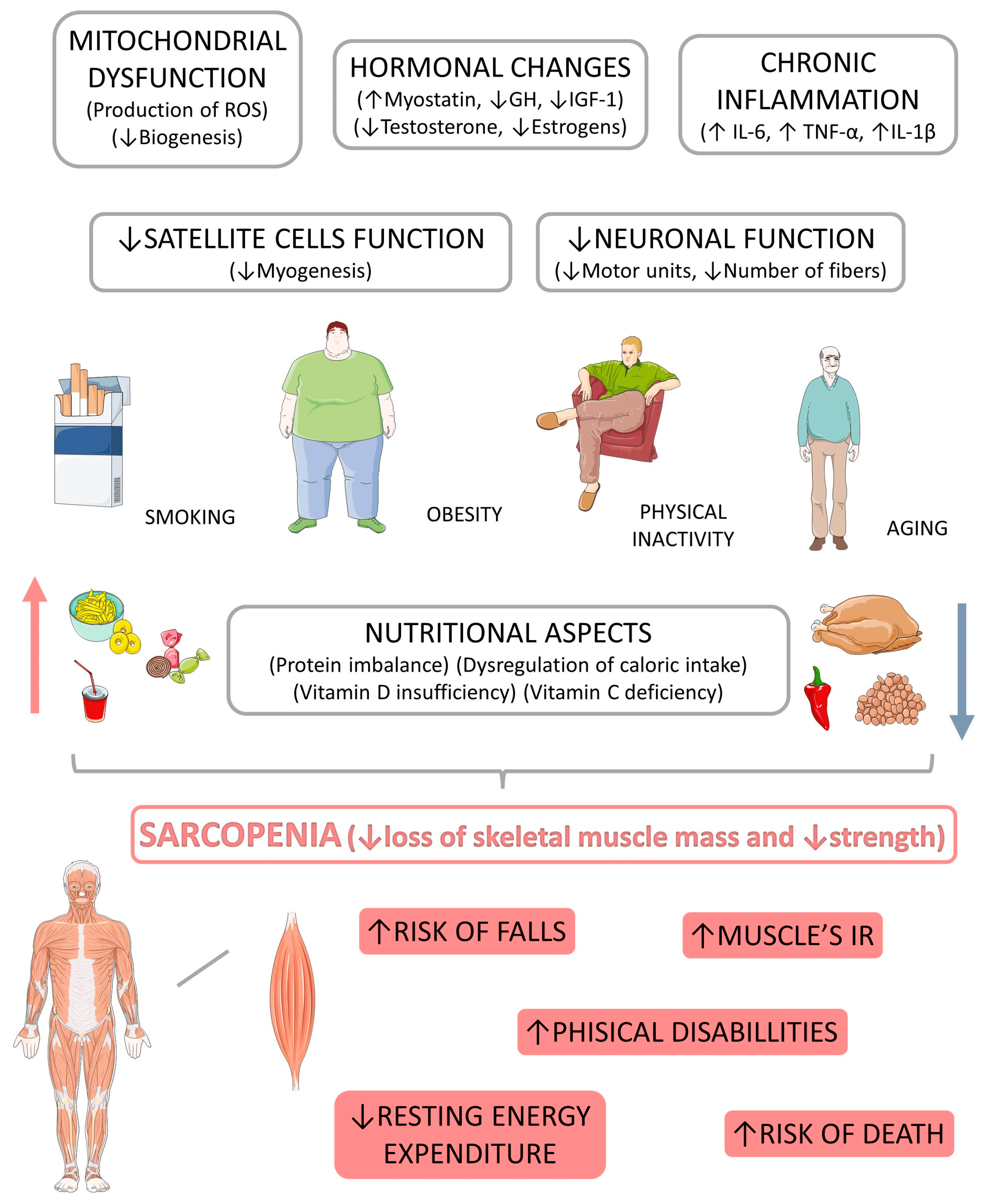

In this author’s previous post, information was provided regarding advanced age (i.e., 65+) and associated changes in strength production, muscle physiology, and quality of life. Left unchecked, such losses compound over time impeding individuals’ health and function. Primary drivers behind such unfavorable changes included a lack of physical activity and decreased appetite (please see The Elderly: Optimal Protein Sources and Consumption for more information). In the following sections, interventions will be explored which help manage incremental and progressive losses of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and physical performance among the elderly; a condition otherwise known as sarcopenia.1(349)

As noted by Mayer et al.,2 the less active an individual is, the earlier sarcopenia-related changes emerge. Furthermore, other detrimental changes manifest with strength losses to include degradation in visual/vestibular skills, balance, and gait; factors, which all increase risk of injury.2(359) Despite a preponderance of evidence linking physical inactivity to sarcopenia and decreased quality of life, solutions do exist. Research indicates that properly constructed strength training protocols for the elderly can counteract the aforementioned age-related impairments.2(359) The following will explore such evidence in greater detail.

A central factor in managing sarcopenia is increasing force production/strength via increased muscle mass.2(359) Of particular interest is the tendency of the elderly to adapt to strength training on a level comparable to younger individuals; a promising and reassuring outcome to those who might have doubts regarding the efficacy of strength training amongst advanced aged populations.2(359) As a general concept, it is known that increasing force production increases muscle mass. However, elucidating exercise intensity/frequency/and time which stimulate such changes, while minimizing risk of injury, is paramount.

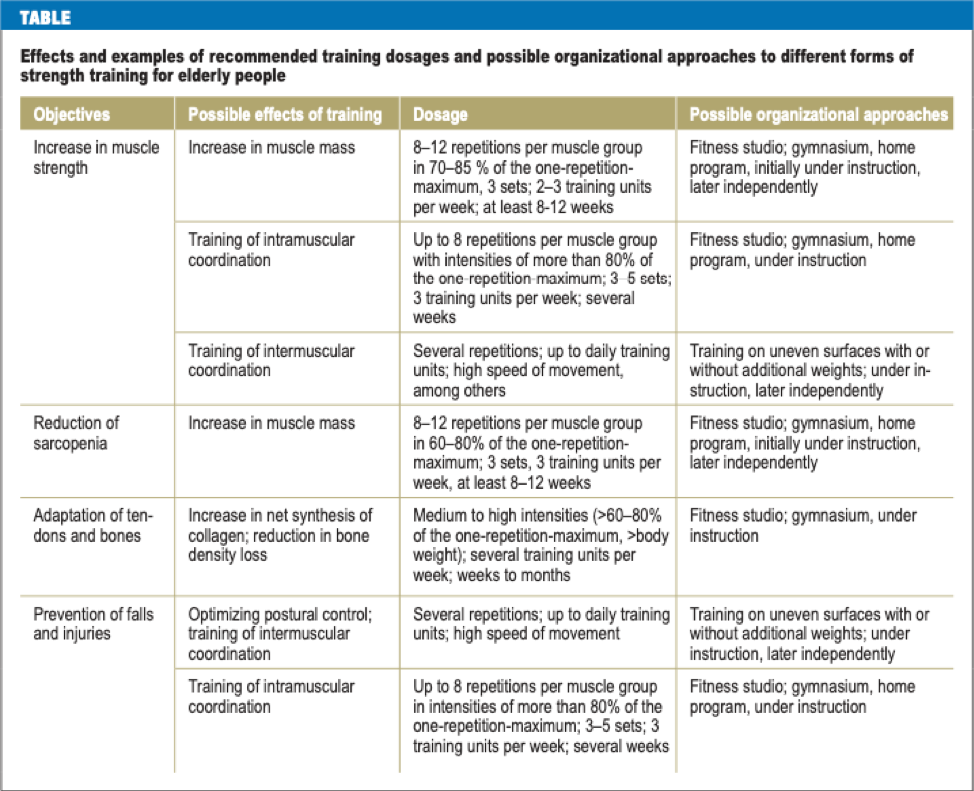

Evidence has suggested that 20-30 minutes (time) of resistance training 2-3 times per week (frequency) had favorable effects upon sarcopenia.2(360) Moreover, such an approach also induced positive changes upon osteoporosis, diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disorders.2(360) Of particular interest is said changes, specifically muscle size, were observed in as little as 6-9 weeks of resistance training.2(360) However, muscle volume was preceded by a rapid increase in strength during the first few weeks, suggesting that strength can improve relatively quickly.2(360) Such is thought to emanate from increased efficiency of motor units/neural adaptations.2(360)

Mayer et al.2(361) suggested that in order to increase muscle mass, repetition ranges were recommended to be between 8-12 at 3 sets per exercise over a period of 8-12 weeks. Loads were recommended to be between 70-85% of a one-repetition maximum.2(360) If sarcopenia was diagnosed and present, repetitions (8-12), sets (3), training frequency (2-3 days), and overall time frame (8-12 weeks) remained the same. However, intensity of exercise was suggested to be 60-80% of a one-repetition maximum. Exercises can include bodyweight, resistance bands, machines, and free weights to facilitate such changes.2(362) Please see the table by Mayer et al.2(361) for further details:

In conclusion, individuals of advanced age (i.e., 65+) tend to exhibit associated decrements in strength production, muscle physiology, and quality of life. Left unchecked, such losses compound over time impeding individuals’ health and function. Primary drivers behind such unfavorable changes include a lack of physical activity. However, evidence strongly suggests implementing a well-constructed strength training program can counteract muscle loss and strength in addition to managing bone density, visual/vestibular skills, balance, and gait. Ultimately, such knowledge should provide insight, hope, and a means to improve strength, health, and overall quality of life.

References

1. Keller K, Engelhardt M. Strength and muscle mass loss with aging process. Age and strength loss. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;3(4):346-350. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3940510/. Published February 24, 2014. Accessed August 6, 2021.

2. Mayer F, Scharhag-Rosenberger F, Carlsohn A, et al.: The intensity and effects of strength training in the elderly. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108(21):359–64.

doi:10.3238/arztebl.2011.0359.

-Michael McIsaac