Tensegrity can be thought of as an aggregate of compressive and tensile forces, which induce stability (Levin, 2002). Tensegrity not only exists at the cellular level; research has supported a link of the cell to the extracellular matrix, thereby affecting the behavior of other cells it is connected with. Moreover, observations have also suggested a hierarchical relationship (i.e., cells-tissues-organs-organ systems-organisms) that emanates from cell to cell connectivity and builds to the level of the organism, in its entirety (Swanson, 2012).

Considering the tensegrity model, and the interconnected nature of cells, tissues, organs, organ systems, and ultimately the organism, such a model may be used to explain how dysfunction at one region, may cause dysfunction/pain at a more distant region in the human body. The aforementioned concepts will be explored by considering the relationship between low back pain and hip dysfunction, using the tensegrity model.

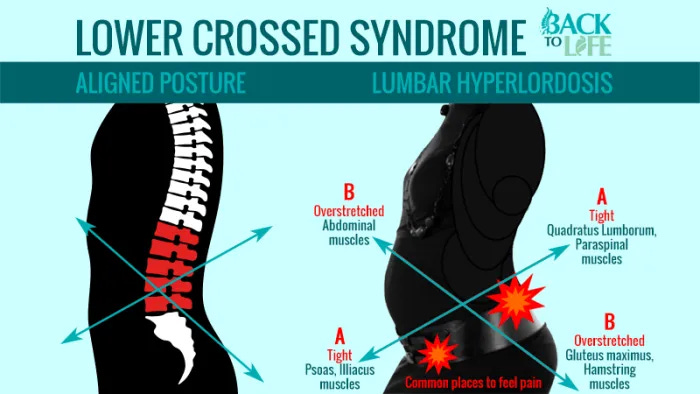

Vladimir Janda was a physician who, in the late 1900s, found trends in joint actions and muscle imbalances. He defined these as upper crossed and lower crossed syndromes (Page, Frank, & Lardner, 2014). Please refer to the following illustration:

Janda observed a relationship between the anterior and posterior sections of the body. Considering the lower half of the body, the abdominals of the anterior side, and the gluteus minimus/maximus/medius of the posterior side tended to be inhibited. Conversely, the rectus femoris/psoas of the anterior side and thoraco-lumbar extensors of the posterior side tended to be overactive/facilitated. Thus, a crossed pattern of inhibited and facilitated muscles exists. Colloquially, this is referred to as lower crossed syndrome (LCS) (Sahrmann, 2002).

Sahrmann (2002) noted that an individual with LCS would likely present with a hyperlordic curve in the lumbar vertebrae, with an associated extended abdomen. The person may also present with low back pain, and symptoms may increase when standing or reaching overhead (Sahrmann, 2002). The aforementioned symptoms might be due to the increased lumbar extension such movement patterns would impose. Associated diagnoses may include spinal stenosis, facet syndrome, degenerative disc disease, spondylolysis and osteoporosis (Sahrmann, 2002).

Tensegrity can be applied to LCS in that hyperlordosis of the lumbar region occurs because of the anterior pelvic tilt of the pelvis. The anterior tilt of the pelvis could be traced back to the shortened/overactive psoas muscles. Thus, shortened/overactive psoas, anterior pelvic tilt = hyperlordic lumbar spine and low back pain. The aforementioned trend is by no means an all-inclusive cause of low back pain. However, it can be used to help explain how different tissues (i.e., muscles and associated bones) share a physical connection between each other (i.e., anterior hip), and more distal regions (i.e. posterior low back).

Applying the model of tensegrity encourages exercise professionals and medical professionals to look beyond singular regions exhibiting pain or dysfunction; such a paradigm shift encourages us to consider the kinetic chain in its entirety, and its involvement in faulty movement patterns. In essence, embracing the application of the tensegrity model reminds us that the human movement operates as a unified system, and that many joints/muscles/fascia/tendons/ligaments may contribute to human movement dysfunction, beyond seemingly obvious sites of poor motor control and pain.

References

Levin, S. (2002). The tensegrity-truss as a model for spine mechanics: Biotensegrity. Journal of Mechanics in Medicine and Biology, 2(3/4), 375-388.

Page, P., Frank, C., & Lardner, R. (2014). The Janda approach to chronic pain syndromes: Preserving the teachings of Dr. Vladimir Janda. Retrieved January 25, 2014 from http://www.jandaapproach.com/the-janda-approach/jandas- syndromes/

Sahrmann, S. (2002). Diagnosis and treatment of movement impairment syndromes (1rst ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Inc.

Swanson, R.L. (2012). Biotensegrity: A unifying theory of biological architecture with applications to osteopathic practice, education, and research- A review and analysis. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 113(1), 35-51.

-Michael McIsaac